Daron Nefcy

Bring a Character to Life

It took Daron Nefcy, creator of Star vs. The Forces of Evil, years to hone her pitch—literally. The first time she pitched Star in 2007 for the Cartoonstitute project at Cartoon Network, she was “super intimidated” because she was presenting to people whose work she admired, namely Craig McCracken (The Powerpuff Girls, Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends) and Rob Renzetti (My Life as a Teenage Robot, Gravity Falls). Though the pitch didn’t lead to a full pilot, the duo was encouraging and she felt that the experience helped build her confidence.

When she first pitched Star to development executives at Disney, Nefcy went in with all the characters drawn out and lots of illustrations. Disney initially responded well to the style of the drawings and Star’s character. But right before she went in to pitch it to Eric Coleman, SVP of Original Programming, Nefcy was asked if Star could be older, a teen, and if her imaginary magical powers could be real. She was thrown, but she went in to pitch it on the fly with these new elements. Her impression afterward was that it didn’t make sense and that she’d blown her opportunity. She went away for a week, took all the notes and created basically the version you see on TV today. What was important for her was that she felt her character, Star Butterfly, had not changed in essence — she was still a very quirky, determined, confident teen.

“It’s important to try to use every note you get to make the show better,” she says. “As long as it doesn’t change the essence of it, or what’s important to you, I think it’s worth exploring.”

When faced with rejection, Nefcy’s response has always been to keep going and come up with other strategies. After Star had been rejected a couple of times, instead of being disheartened, she turned the concept into a web comic. She explains that sometimes it feels as if the characters just want to live. “So even if [Star] was going to exist as just the web comic, I was going to execute it somehow,” she says. The work paid off.

Nefcy believes that you need to be able to strike a balance between being flexible and able to make changes, but also to stand up for your ideas. She emphasizes that your vision has to be strong and you need to recognize when change can improve it, or when you feel it won’t work.

When pitching, she says, well-developed characters, who have an interesting rapport with each other, are essential. The task is to convey why anyone would want to watch these characters week after week, or as happens nowadays, for a whole binge-watching session. She feels pitches shouldn’t be longer than five to 10 minutes to get your idea across.

Nefcy prints out of her bible so she can flip through it during the pitch; she finds it’s easier to remember what she wants to say if she has a drawing at hand. The pictures keep it fun and exciting and help others remember it too. She thinks it’s helpful to have a short paragraph below each character explaining who they are, how they interact, as well as a few sentences describing the world of the show.

And, she adds, try to look at pitching as a positive process — even if your idea is rejected, you’ve at least made a connection.

“I think that if you’re coming up with an idea just because you think you might sell it, it’s probably not going to resonate with people,” she says. “It has to come from your heart. It’s kind of like a child in a way, I think you have to really love them.”

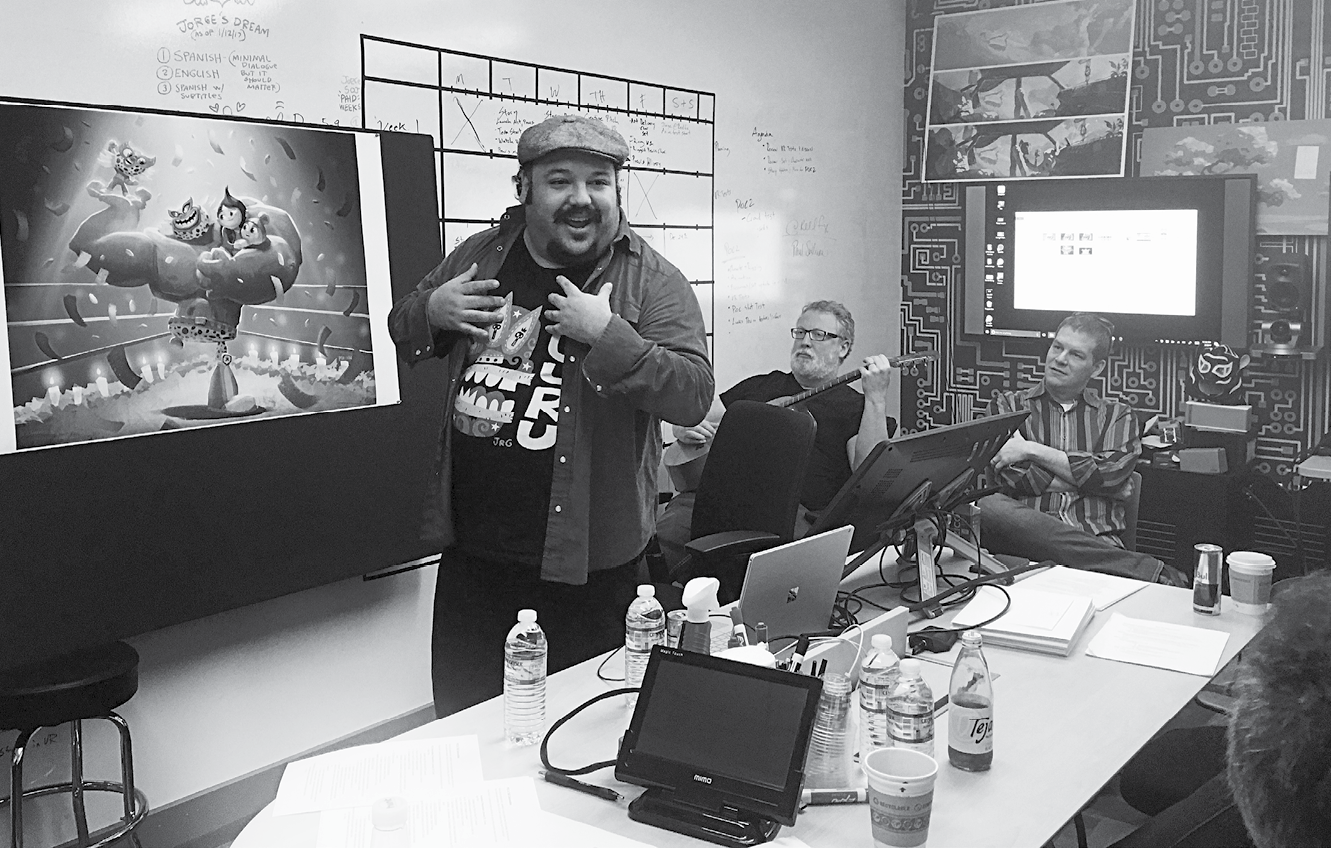

Jorge Gutiérrez

Capture the Power of Culture

Time and time again, Jorge Gutiérrez was faced with rejection. The director of Book of Life and co-creator with his wife, Sandra Equihua, of El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera, says, “My culture has always been this thing that I was warned would hurt me and I thrive on being told I can’t do that,” he says.

Gutiérrez has always been inspired by Mexican folk art and pop culture and it features strongly in his work. In fact, it helped him get into CalArts.

“I showed up with a portfolio [of] a bunch of art work that I thought was what Americans wanted to see,” he says. He had drawn cartoons that were his version of Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and The Simpsons. So when CalArts reviewed his work, he was told: “All your drawings are crap. You have no voice.”

It was his portfolio of Mexican paintings that garnered him admission to the school. However, once there his teachers told him: “You’re making this Mexican stuff, no one’s going to hire you.” And they turned out to be right. When he showed his portfolio to the studios, they would admire his work and then ask for his “other stuff.” At one point, he was told: “If Scooby-Doo goes to Mexico, you’re the first guy we’re going to call.”

Gutiérrez was determined to stay true to his vision and a piece of advice from a producer at Nickelodeon helped guide this effort. The executive took him aside and encouraged Gutiérrez to pitch his own shows, “because if you don’t pitch it, no one is going to make this type of stuff.” What he initially thought would be his weakness, being from another country and an outsider, turned out to be his strength. He adds with a laugh, “It’s like animation judo. I just said, ‘Well, I’m going to turn that into my strength.’”

“My culture has always been this thing that I was warned would hurt me …”

Gutiérrez first started pitching ideas for movies and hit a wall — no one was interested; however, he gained traction with a concept he co-created with Equihua, about a teenaged Mexican superhero. El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera received multiple awards and studios started approaching him to do a movie.

“At that point studios were basically saying, hey, now that you have a TV show, would you be interested in making movies?

The difference between pitching a movie and pitching for television, Gutiérrez explains, is that with a movie, the focus is on the three-act structure.

And would you happen to have a Mexican movie that you’d want to make?” He took the exact movie he’d pitched seven years earlier, and “I just ripped off the first page and wrote a new date, put it back on.” This time the response was different, ultimately paving the way for Book of Life, his first full-length film.

“So when you pitch your story you have to hit those big moments. What is the movie about? What do the main characters want that they can’t get? And how does the movie resolve?” he says. Adding, if you don’t have answers to those questions or if you give “topsy-turvy answers” then you’re in trouble. He also explains that it can be a lengthy process — if you’re successful in a pitch, then you get to pitch to that person’s boss and so you proceed up the chain of command. No one is going to say yes, we will make it. Rather, they will say, yes, we’re prepared to spend a small amount of money to see if this is worth it.

Gutiérrez says to assess notes and make sure they make sense. “A lot of time they might be testing to see how collaborative you’re going to be,” he says. For example, they might even throw a bad note on purpose to see how you’ll react. “They don’t want you to say yes to everything — but don’t want a jerk who’s not going to want be collaborative,” he says.

The best advice he’s ever been given is that when you hear an idea in the room—you should take your emotion and yourself out of it and try to really consider if it makes your show better. Even though it’s difficult, he tries to look at every note as an opportunity to improve his work.

“So as much as I want to punch the wall, smash my computer when I hear a bad note, I say, okay, this is an opportunity to make it even better,” he adds. “I wish someone had told me that rejection makes you stronger. Because I took it really personally at first and it really hurt. But it’s part of the process.”

Craig McCracken

Connect with the Audience

Craig McCracken, award-winning creator of shows such as The Powerpuff Girls, Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends, and Wander Over Yonder, had an experience early on with his first pitch that subsequently influenced his process. It was for the first Powerpuff short for Cartoon Network back when it was the Warner Cartoon Program. Craig was invited to a focus test of the seven-minute short.

“I was in this focus test with this group of 11-year-old boys and they watched my pilot and they hated it,” he says. “They really said, ‘This is the worst cartoon that’s ever been made, whoever made it should be fired!’”

McCracken took the response to heart and tried to understand why they were so frustrated and angry. He did some soul searching and thought about how to communicate his idea better to a younger audience. “I basically redesigned the The Powerpuff Girls. I gave them fingers, I made them look like real kids. I just thought they were too weird,” he adds. But then he got a call from Mike Lazzo of Cartoon Network who advised him against his changes: “He said, ‘Craig, don’t do that—we really love your vision. We don’t want you to compromise who you are just because you had a bad focus test.’”

The extreme reaction showed he’d hit a nerve with the audience and Lazzo believed that the kids really wanted to like it—only Craig wasn’t giving them all the right information but he was on the right track. In the end, Craig realized the short was a little tongue-in-cheek and the humor was a little too sophisticated for kids. He’d also never explained why the girls had super powers, or what their home life was like. So when he did the The Powerpuff Girls series, he decided to “pull out the artsy-fartsy-ness and just do a sincere story about little girls being superheroes.”

“Sometimes you have to hear the note within the note …”

McCracken has been at both sides of the table when it comes to pitching. He was part of Cartoon Network’s Cartoonstitute program together with Rob Renzetti—and had people pitching to him. He describes how in that position “you are at the mercy of what the network is looking for at that particular time. You may have someone who has a really great concept and ideas, but it just doesn’t happen to line up with what the network is looking for.”

He encourages anyone pitching to bear in mind that studio agendas morph and that what might not be a good fit at one studio, may be exactly what another is looking for. If your project is rejected, McCracken says, the main thing is not to beat yourself up and to remember that people say no for a variety of reasons.

Part of the pitching process is learning to gauge how people respond to material. McCracken remembers that the idea that would become Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends was completely different when he first pitched it. “I just wanted to get regular people and imaginary friends hanging out in the real world,” he says. “That was my goal for a show.”

“You’ve got to read who you’re pitching to and get the right response from them.”

The original idea centered on young parents with a baby who conjured up imaginary friends for each of his emotions. Craig ran into Linda Simensky, the head of development at Cartoon Network at the time, and pitched her the idea. “She kind of smiled a little bit—but I could see the wheels turning in her head,” he says. It hadn’t really connected with her.

McCracken went home and thought about why it wasn’t resonating and what he needed to change. It was then that he realized the show should be about kids giving up their imaginary friends leading to the idea of the foster home for imaginary friends. The new concept worked better as a vehicle for reaching his goal. He pitched Simensky his new version, “and she immediately laughed,” says McCracken. What he’d needed was a simpler pitch that demonstrated the show was more kid-friendly. McCracken adds: “You’ve got to read who you’re pitching to and get the right response from them.”

Craig recommends—and it’s something he tries to do with each show—trying to distill the essence down into a sentence or seven words. Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends happens to be a perfect example, because the title itself was the pitch. It’s invaluable to have a quick way of describing your show, a real hook that instantly tells the audience what it’s about. Once they’re hooked, he says, details, character development and complexities that you have will serve to enhance the basic idea.

If he’s been given notes, Craig always asks: Do these notes make it better or different? If the notes actually make it better he’ll think about incorporating them.

“If it’s just making something different I don’t implement them because that’s just one person’s opinion,” he says. He believes that if you implement every note you get in the room, you’ll be taken so far from the original vision of your project that it loses sincerity. Experience has taught him that “sometimes you have to hear the note within the note.” Often, Craig says, the solution offered to the problem might not necessarily be the right solution, so he tries to figure out the bigger issue and address it.

Whether it’s a little film, a lot of drawings, some animated scenes, or even a comic and some gags, McCracken recommends going into a pitch with something that shows what your intentions are creatively—something that demonstrates your sense of humor or the style of filmmaking you’ll be using and gets across the vibe of your show. It’s something he tries to do every time he pitches.

With The Powerpuff Girls he presented his student film, with Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends he filled a room with artwork, character vignettes and little gags. With Wander Over Yonder, he had half of a graphic novel that he had written and drawn that he could hand to Disney. He would encourage people to invest the time to produce this sample material because if you pitch an idea just verbally, then you run the risk of people misinterpreting your creative intentions. You’re then essentially at the mercy of their imagination.

He once had the experience where an idea he pitched to a company was greenlit and when he turned his pilot in, the response was, ‘Wow we had no idea that’s what you intended to do with it. We saw it in a totally different way.’ Happily, they loved what he had done with it but it served as a lesson learned.

Photography by Tim Sullens.