“It was an idea that I had been formulating for a while about characters that interact musically without dialogue,” says Segurson. Growing up in a melodic household—his father Howard is an alto sax player and his mother Harriet, a singer—Segurson was influenced by his dad’s musical tastes.

“My Dad is from the be-bop school of west coast Jazz,” says Segurson. “He first turned me on to Duke Ellington when I was really young.” His father also told him stories about his great grandmother (whom he never met) and how she called jazz, “the Devil’s music.”

Segurson’s developing musical tastes also influenced the cartoons he watched. He was mesmerized by reruns of Popeye’s color feature series, a trio of cartoons based on stories from The Arabian Nights. The cartoons, each 16 to 22 minutes long, debuted between 1937 and 1939 and showcased Sammy Timberg’s jazzy score along with a rhythmic base of Arabian music.

“There’s something about what they call hot jazz that was used by Timberg, which I really love,” he says.

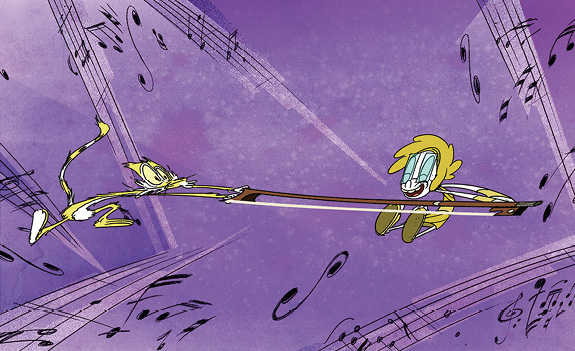

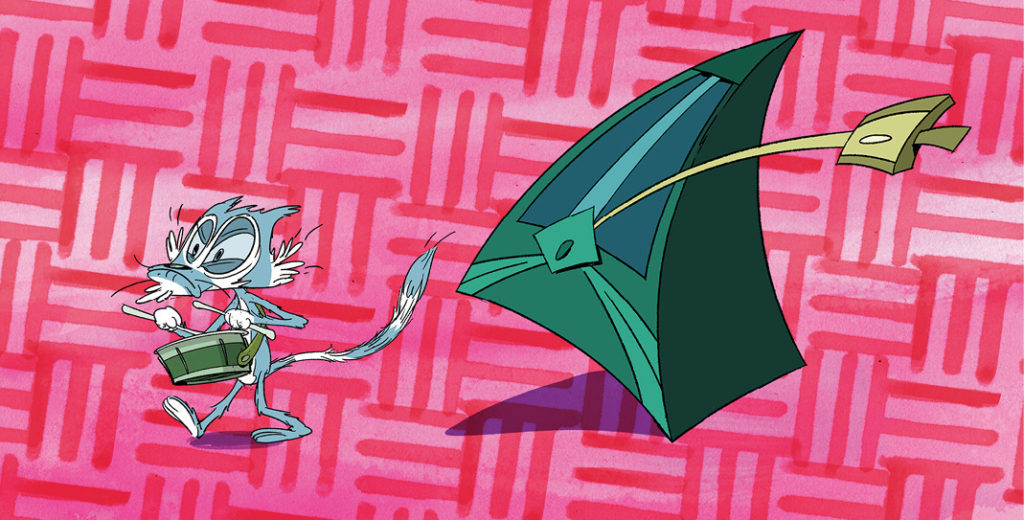

All these influences percolated in Segurson’s mind as he brewed up a story for the short, a musical battle between classical European styling versus American jazz. A tale emerged of an aging King, who feels his son has no sense of order ever since he started listening to jazz records. In an effort to regain control over the Prince, the King hires Mr. Whiskers, the best music teacher in all the land. The King temporarily thinks he’s solved the problem but then chaos ensues when the Prince and Mr. Whiskers begin their musical battle.

“The King is worried about the kingdom and responsibilities—that kind of mirrors classical music that has order and time signatures versus jazz which is based on syncopation and improvisation,” says Segurson.

An Arabian Nights setting—a partial ode to the Popeye cartoons—seemed like the perfect setting. But there was another ambitious idea that Segurson wanted to implement—he wanted to integrate 2D animation with a stop-motion world.

Set in Motion

“When I pitched this short I actually didn’t tell them that I wanted to do it with stop motion,” admits Segurson, who convinced the team at Nickelodeon to move forward with the technique after it was accepted in the shorts program.

“Nickelodeon was impressed with Cosmo as a filmmaker, and we were intrigued by the idea of a short that used little dialogue and instead used music to tell a story,” says Chris Viscardi, Senior Vice President, Animation at Nickelodeon. “It was not so much the technology per se, but rather Cosmo’s passion for using this approach to tell his story. Since we are a creator driven studio, we love looking for opportunities to have creators tell their stories in unique ways.”

For Segurson that vision was rooted in stop motion but he emphasizes that it wasn’t simply a fanciful idea, it plays an integral role in the story.

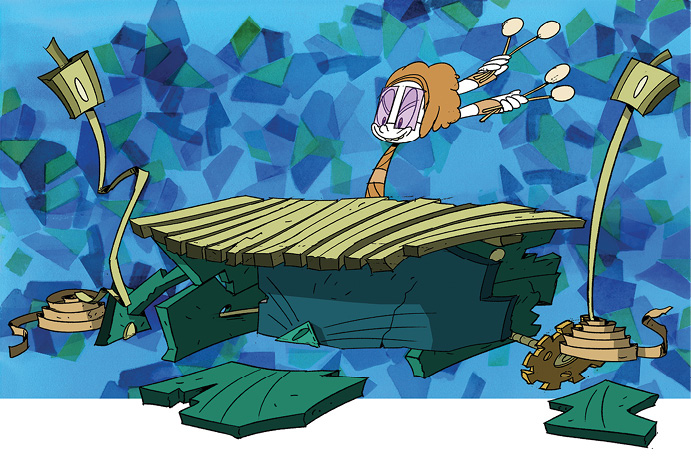

In the middle, a surrealist 2D battle takes place between the snooty Mr. Whiskers and the Prince. “It was going to go beyond physical space,” he says, so it was important to establish a difference between the “real world” and the fantasy world of the battle.

“I decided to use stop motion sets for the palace—the reality that the King lives in—and then create this [abstracted 2D] fantasy world that the Prince lives in when he’s playing music,” he says.

With Nickelodeon’s approval, Segurson, who had just wrapped up co-directing Rocko’s Modern Life: Static Cling (a reboot of the original ‘90s series), got to work on creating a three-dimensional world for his characters. However, this short wasn’t Segurson’s first foray into stop motion. His love for the technique started as 6-year-old when he saw the Rankin/Bass-produced Mad Monster Party. By the time he was in high school, he was using a friend’s video camera to create his first stop motion film.

“You couldn’t take stills,” he says, “so we were moving [marshmallow] Peeps around the camera and then edited out our hands.”

As a professional artist he was hired by a San Francisco foodie to create stop motion vignettes for a website—real strawberries jamming on musical instruments, cheese being chased by graters. Throughout, he experimented on his own learning the craft through trial and error. Then in 2014 he worked for Screen Novelties (a non-union studio) on Elf: Buddy’s Musical Christmas.

“I ended up storyboarding that entire project on site so I was able to board out a gag and stage a scene then walk in the other room and see it being filmed—see how my staging was interpreted by a stop motion animator on a real set with real lights,” he says.

He was also introduced to Dragonframe, which he calls invaluable to anyone interested in the technique. All of these experiences provided Segurson with the foundation to move forward with the project, and Nickelodeon was supportive of the endeavor. Indeed, Viscardi says the studio would like to explore the use of stop motion more but emphasizes, “it needs to be driven by the vision of the creator.”

Getting Down to Business

After sitting down at his organ and working out compositions and musical themes for each character that evoked the Golden Era of jazz, Segurson started sketching characters and thinking about how they were going to move within the physical spaces. He storyboarded the entire project, devoting much of his time and plenty of revisions to the musical battle, then created the animatic. With a tight budget, he didn’t want to build superfluous sets.

It was only then that Segurson could literally roll up his sleeves and get to work. He started calling on a group of close collaborators. He reached out to saxophonist James King, co-founder of the band, Fitz and the Tantrums. The two met at CalArts: “He and I used to go into the music rooms and make each other laugh with different [cartoon] themes so I knew he was the perfect collaborator.” Together, they composed and recorded a temporary click track to serve as a guide for the action.

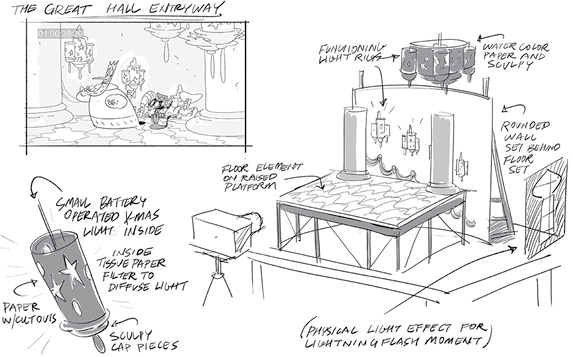

Next, Segurson called on Mark Chamness to build the sets. It took two weeks and plenty of cardboard and PVC to create the six key locations—the exterior of the palace, the stairs leading to the Great Hall, the Great Hall, the Music Room, the King’s quarters and the interior of the limousine. They got creative with materials.

“I hit up local thrift stores and found junk jewelry beads for door knobs, a couple of gaudy old lady shawls for curtain materials, Christmas ornaments for castle spires, and a domed 7-11 Slurpee lid for chandelier parts,” he says.

The team spent the next month painting and texturing the sets. They also had to track down miniature props. Segurson found a line of French Provincial dollhouse furniture that could be transformed into a different treatment to match the rooms, but still there were props that he couldn’t find, such as the Victrola phonograph.

“When I pitched this short I actually didn’t tell them that I wanted to do it with stop motion …”

Nickelodeon’s 3D printer turned out to be the perfect solution. Segurson created sketches and sought Frank Rocco’s help to interpret the designs into Maya, who sent the new files off to the printer. Other challenges presented, he needed to create a working doorknob that the 2D characters could interact with.

“There’s something really exciting about creating something from a bunch of cardboard and paint and then putting it on a set, lighting it and putting a lens in front of it,” he adds.

The entire production would be filmed in a small room, about 10 feet x 12 feet, on the 4th floor of the Nickelodeon building. “I built perspective into the design knowing that I would have a limited amount of space,” he says. For example, he designed the floors skewed so they already had a push perspective and gave the spaces an air of palatial grandeur.

The animatics became the basis of the timing determining how the characters would move across the set. For example, there are several scenes where lightening strikes as the characters move either across the Great Hall or up the stairs leading to it. In the scene with the Great Hall, Segurson wanted rain pelting outside the ornamental windows.

Rocco, who had worked in special effects in the ‘80s and ‘90s, suggested scratching clear cels and lighting them to mimic a torrential rainstorm. In every frame, Segurson would swap out one of about a dozen scratched cells while Director of Photography Aaron Wise slid the camera 2mm per frame to keep the movement smooth. They outfitted the track with a little wire arrow and laid down a tape measure alongside it to create a homemade rig. It was an exercise in patience.

“That five second shot took about two hours,” says Segurson, “and we shot it three times.”

Another shot where the King opens the door to the music room and reveals his son playing the drums proved to be the most complicated in the short with three layers of action occurring simultaneously. The King turns the doorknob (interacting with a physical object), pulls the door open while the camera is still moving forward and reveals the action on the other side of the door.

The knob, a bead less than a quarter inch in size, had to be moved incrementally by Segurson. He rigged the two beads with a wire taut enough to turn. They also had to determine exactly how many frames were needed to move the camera past the doorframe. On the other side, the Prince is playing wildly on a set of drums, that are a real prop, but the cymbals are animated in 2D. However, when the camera cuts to the close up the cymbals are physical objects. Each movement was mapped out on an x-sheet and the timing determined with the help of animation director Andrew Overtoom.

“I needed the elasticity of 2D animation to keep up with the pace of the characters and the energy I wanted them to have,” says Segurson. He also wanted the characters to squash and stretch like in the cartoons from the ‘30s and ‘40s.

In some cases, Segurson storyboarded the action twice—once before and once after the shoot—to provide flexibility for on-set improvisation. Segurson would then import stills from the shoot and line up the new shot with the storyboard that served as a blueprint for the 2D animation, which was all hand drawn.

In order to achieve an expansive shot towards the end of the film, the team had to shoot the model without a ceiling in order to light the space appropriately. Segurson chose to matte paint a ceiling—a trick from a bygone era of filmmaking—over a stop motion chandelier that swings to the beat of the music.

Though the click track helped syncopate the actions to the story, the final music heard in the short will be recorded by a session of jazz musicians playing to the final picture, reminiscent of Carl Stalling in the old Warner Bros. days.

“People will want to watch the short multiple times because of the amount of detail that we’ve put into it,” says Segurson, who has devoted almost two years to the project. It’s clear this 4½-minute short is a labor of love or perhaps more appropriately an ode to it.