“Shrink me down and let me live here, please,” comments an Instagram admirer in response to one of Dave Creek’s beautifully constructed bonsai treehouses. It’s not an unusual request as anyone who views these whimsical creations can’t help but imagine what it would be like to actually inhabit them.

Creek, a character designer on Bob’s Burgers, began creating miniature treehouses in bonsai trees 15 years ago, an activity that developed separately from his journey into the world of animation. Creek graduated from CalArts and freelanced for about five years, doing hand drawn animation and design until a producer asked if he would like to work on a network animated TV show she was starting. The show happened to be Bob’s Burgers. “I just lucked out [on] timing and knew the right people,” he says. Almost 10 years later he’s still working on the show and also teaches a film workshop class in the Character Animation department at CalArts.

Creek’s treehouses, on the other hand, are a passion project that provide a creative outlet completely separate from his animation work. Creating bonsai treehouses is a Zen-like activity that he finds therapeutic. “When you’re working on them, you can’t really think about much else,” he says.

His obsession with treehouses started in childhood. Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, he was always out in the woods, climbing trees and building forts. He learned basic building from his carpenter father who frequently took him along to job sites. When he moved to California, he missed the outdoors and so turned his attention to bonsai trees, which he’s always seen as an artistic collaboration with nature.

Older bonsai trees are expensive and can range in price from $8,000 to $25,000. That financial cost, coupled with the inherent problems of creating a fixed structure around a growing tree, are the reasons Creek opted to use dead bonsai trees instead. He has suppliers from Southern California all the way to Washington and Florida. The tree he’s currently working on belonged to fashion designer Tom Ford. When the tree couldn’t be saved, Creek bought it for a fraction of the price.

After selecting a tree, he meticulously preserves it with resin, much the same way a museum would preserve a wooden artifact. It’s an arduous task that involves volatile chemicals, gas masks and time. But once it’s done, Creek is left with a piece of wood that’s “pretty much everything-proof”, while still looking natural. It took 100 hours to complete the preservation on the current specimen he’s working on, while a smaller bonsai tree might take 25 hours.

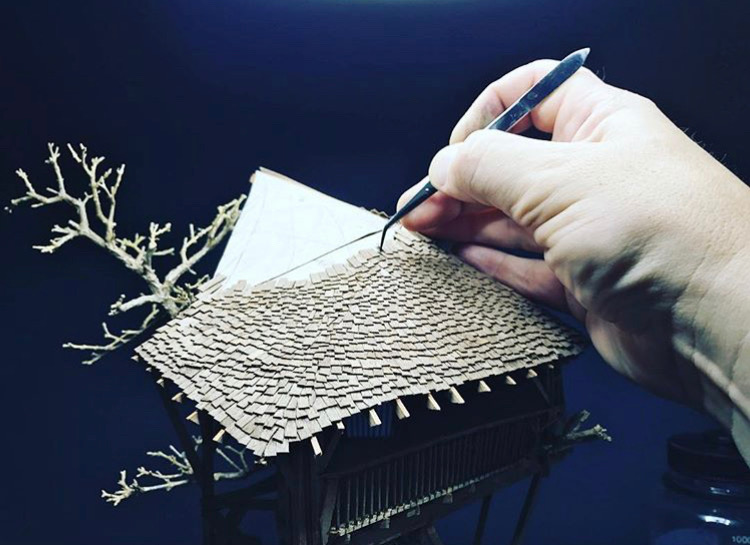

Building the treehouses themselves takes endless amounts of patience. Creek uses specialty micro-milled wood that he sources from Pennsylvania and Australia. The tools he uses, though, are simple and include an X-Acto knife, tweezers, files, and a cutting jig. Despite working an eight-hour day, he still has the energy to do very detailed work at night on his treehouses. Sometimes he wonders if his neighbors think he lives with several different people because he frequently has loud arguments with his trees when they’re proving difficult to work with. When the urge to get out of LA strikes, Creek heads out in a van he’s converted into a mobile art studio/adventure wagon. With this setup, he can park in a quiet spot in nature and work on his treehouses, accompanied by his buddy, Chop, an American Staffordshire Terrier he adopted three years ago.

It took Creek over ten years to complete his first treehouse and he estimates that his current project will take 2,500 hours in total. His “first born” was fun, whimsical and less structurally realistic than his later creations. That one caught the eye of treehouse master builder, Pete Nelson, who snapped it up.

Interestingly, Creek doesn’t work with plans or sketches. “It’s all on the tree,” he says, “It might have one good spot, or several.” The one he’s working on now has lots of available space so he’s building nine different cabins on it: “I wanted to fill it out as much as I could without overwhelming the tree.” Often the structures are so intertwined with parts of the trees they give the impression that they’ve grown organically out of them. Creek attributes this to his process. “I don’t look at these things as scale models or miniatures. I approach it completely sculpturally…very, very meticulously one step at a time,” he adds. He does plenty of research on the structure, so that “theoretically this should work in real life, but I have liberties that I take that kind of dodge the laws of physics for the real big ones.”

Creek has exhibited his works at multiple galleries and finds the reaction people have very satisfying. “It’s really great seeing people get swept away when they look at them,” he says. “They automatically just light up, whether they’re eight years old or 80.”

For this reason, rather than putting them up for sale in high-end galleries, he’d prefer to put them in front of the people who would benefit most from seeing them. One of his goals, once he has a larger body of work, is to take them to children’s hospitals and display them there. He can see himself continuing to build them long after retirement and perhaps even touring around the country with a mobile display. Right now, the curious can see more pictures at @dave-creek on Instagram.

Dave Creek passed away on January 7, 2021. He will be greatly missed by his animation family for his generous friendship and great talents.

.png)