One of those kids was Jared Stern, creator and showrunner of Netflix’s recently released Green Eggs and Ham series, who faced a similar but quite opposite challenge: Take a brilliantly simple book and stretch it out to fill 13 episodes of animation—an exciting yet daunting task. Stern had childhood memories of the book’s bright orange cover and that it had appealed to him because it was subversive, whimsical, weird and fun. “The biggest challenge was how to expand something that is so perfectly simple, while retaining the soul of what made it great in the first place,” he says.

When he revisited the book it occurred to him that it’s both an odd couple story—essentially about a grumpy guy who’s closed off not only to green eggs and ham but to everything in life, and a silly guy who is open to trying things—and it’s also a road trip defined by places where Guy Am I refuses to eat the eponymous dish—not in a car, train, boat, or anywhere. The series deals with contemporary concerns, but, he says, “in many ways they are the same concerns Dr. Seuss had when he was writing his books.” In that respect there wasn’t much they needed to do to make it fresh because they were dealing with issues, such as prejudice, that are still relevant today.

Stern had worked on animated features and found the iterative nature of filmmaking to be incredibly valuable. He tried to bring some of that into their process and believes what they ended up with was a hybrid between feature and TV in both the quality of the animation and the style of the storytelling. While four years sounds like a long time for an animated TV show, he points out that for a feature that would be normal.

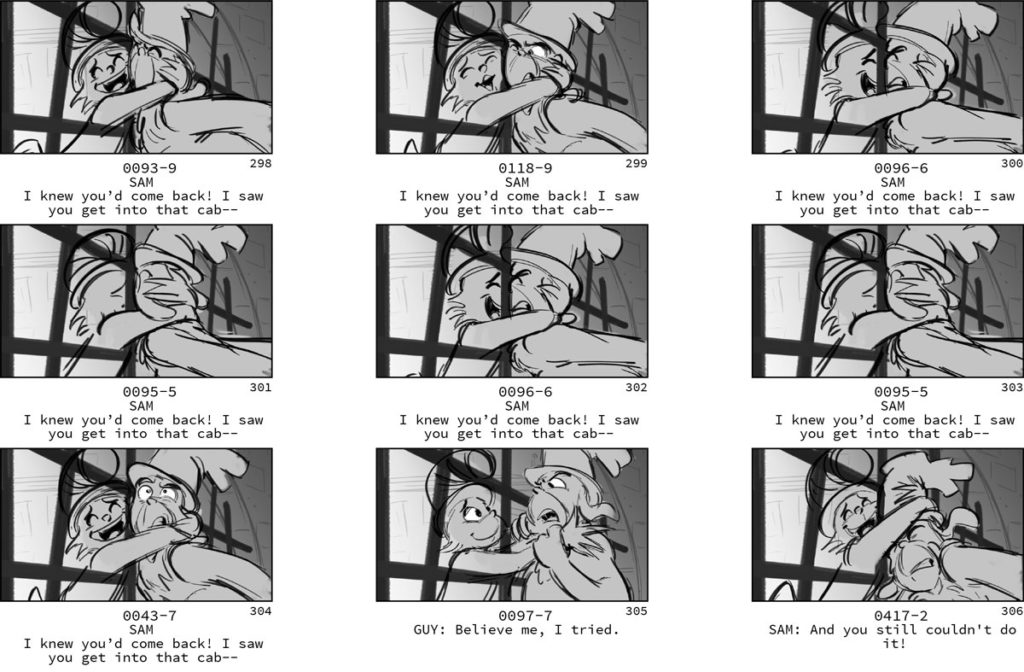

The storytelling took time because they used the feature animation model, going from script to storyboard artists, encouraging them to contribute new ideas. “So it’s like a second writer’s room except they can draw better than us and they’re amazing visual storytellers,” he adds. They would go into editorial from there and do scratch voices to see what was working. After getting notes, it was back to rewriting and more storyboards and only after that would they record the actors. This process was repeated twice for each episode.

Another way Stern wanted to pay homage to Dr. Seuss was by using rhyme. “I’m a big hip hop fan—I don’t know if that’s why it was something that came naturally to me—or maybe because I read so much Dr. Seuss,” says writer Vanessa McGee, who crafted the rhythmic dialogue. To prepare, she also read the author’s biography, which discussed the theory behind his rhyming scheme. McGee says that Dr. Seuss is an icon for a reason—his rhymes look deceptively simple, yet there’s “something inimitable about it…an essence that you’re never going to quite get.” She was deeply conscious of dealing with something that people hold dear and having to handle that with care while still having fun. She loved the freedom of writing for animation, where you can make characters do absolutely anything, even fly, a stark contrast to live action where, “if you dare write a scene that’s exterior night, they’ll be so angry with you!”

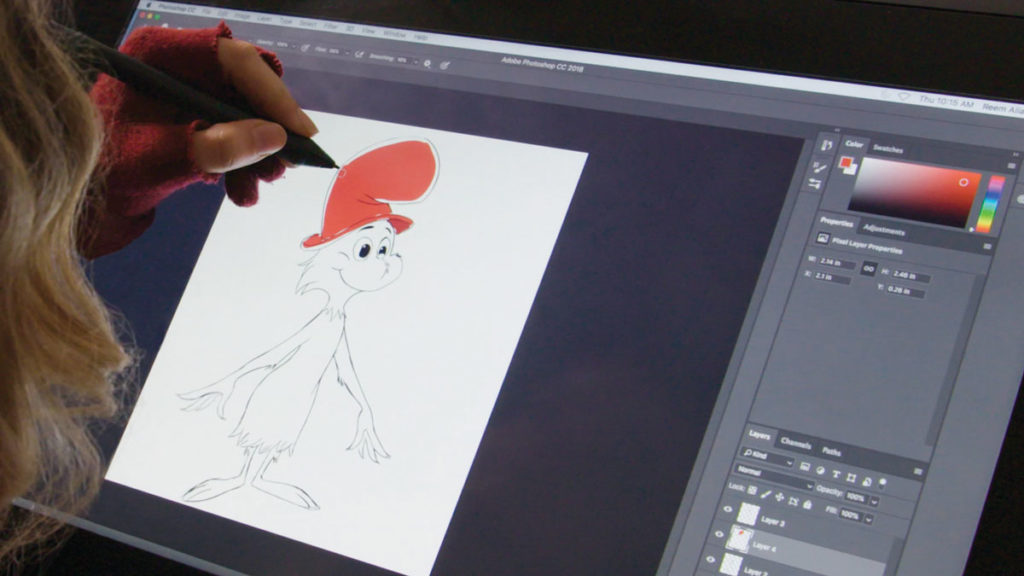

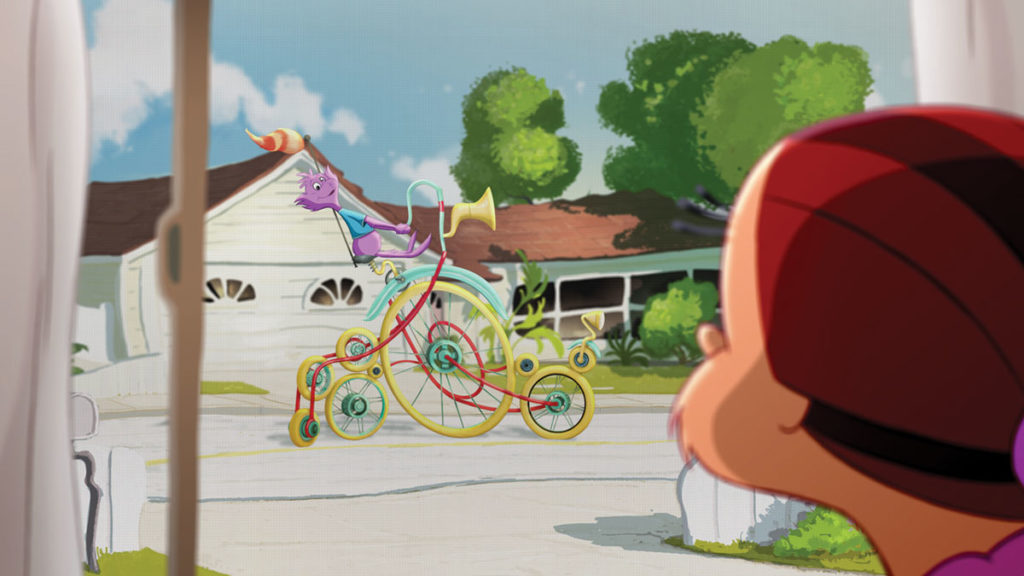

Reem Ali-Adeeb worked as the Lead Props Designer on the series. Born in Syria, Ali-Adeeb only discovered Dr. Seuss as an adult and was “blown away by how simple yet incredibly fascinating his writing was.” Her biggest challenge was to “hit the style” of Dr. Seuss and it took a while to find out exactly how to introduce the old favorite in a new way. When she designed a vehicle or a prop, she’d look at the ‘60s esthetic and then tried to incorporate Dr. Seuss shapes, like the s-curve line that is so prominent in his work.

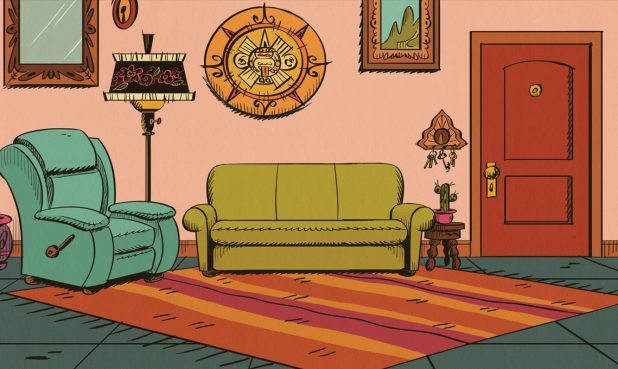

Ali-Adeeb loved the vision of art director Pascal Campion, who wanted the world to be imbued with a sense of realism so that, “it didn’t seem as if everything is made of marshmallows and pillows.” She explains that this approach adds dramatic tension, allowing the viewer to be afraid that the character might actually get hurt. Her favorite prop was the oxicycle, a bike with eight wheels, and she loved working on Guy’s strange inventions—like the anti-umbrella—which has water coming from inside, as well as thinking up different ways to serve green eggs and ham for each episode—from smoothies to breakfast burritos.

Storyboard artist John Anderson was not really interested in going back to television but when he saw the scale of this production, he jumped at the chance. The process was very much like a feature, which gave the show a cinematic feel. “The fun thing about 2D and hand drawn is that you can really stretch it and move it,” he says. Working on it was thrilling because sets weren’t built in a CG environment and so weren’t locked down. “There was so much freedom,” and “every shot was new and exciting because every shot was drawn.” Stern adds, “There’s something beautiful about hand drawn animation that we missed and hasn’t really been done for a broad family audience in this way for a while.” The nostalgia it evokes felt like the right fit for Seuss’s illustration style.

Anderson also found it exciting that the series is essentially one long epic story—the characters didn’t reset at the end of each episode as is common in television. Because they develop and grow emotionally as the story progresses, he had to be constantly aware of where they were emotionally in the story. There was freedom for the actors too, if they did something fun or made a sound, then it came back to board and was reworked.

Stern is quick to credit the 300 talented people who poured their creative energy into the making of the series. The showrunner recalls pitching the series to Geisel’s widow, Audrey, who was in her nineties. He sat in Dr. Seuss’s office filled with the author’s personal belongings, with a view overlooking the Pacific and a “single, perfect Dr. Seussian tree.” It was pretty intimidating but when Stern was done, Mrs. Geisel said: “I wondered how anyone was going to do anything with that one, you know, it’s pretty simple. But you pulled it off.” It was as close as he would ever get to the author who died in 1991, whom Stern believes would approve of what he has done. He hopes he’d say something like, “‘You didn’t screw it up that bad.’” And perhaps he’d say it quite eloquently, in rhyme.

.png)