What role did cartoons play in your childhood?

When I immigrated, I lived with my grandmother and a younger cousin—and watching TV was all I did! I learned English watching SpongeBob SquarePants and PBS cartoons like Sagwa and Dragon Tales. I was a bit too old to proudly admit I watched kids’ TV shows, but at home I loved every moment of it.

When did you decide to become an artist?

I was fortunate to attend a public arts high school in San Francisco called Ruth Asawa School of the Arts. When I was graduating, I learned that it was not financially realistic to attend a private art college for fine arts. A friend suggested I check out San Jose State University for their Animation/Illustration program. From SJSU, I learned that there are many fields within the animation industry. Although I absolutely enjoyed my time there, working on multiple student animation shorts with friends, I struggled a lot finding the right artistic role in the industry. It wasn’t until I came down to L.A. for an internship at Nickelodeon that I really learned what it is like to work in an animation studio. Getting to be in the studio that made SpongeBob blew my mind!

You began your animation career working on backgrounds and color styling on fairly traditional cartoons. How (and why) did you make the leap from that world to your counterculture comic Koreangry.

Koreangry started after a couple of layoffs in the animation industry during the 2016 election. I’ve worked since I was a teenager, so the concept of being laid off was something I wasn’t used to. The animation industry can be inconsistent at times, and learning to accept that aspect of that world helped me focus on my personal work. I wanted to share my frustrations about my career, identity, immigration, family and politics with an anonymous character. Koreangry helped me be comfortable about what I was going through.

Why did you choose three-dimensional puppet/armature for Koreangry? Why not a more classic style of animation?

I was always enamored with Wallace & Gromit and that old-time textured stop-motion. During college, I took a CSU Summer Arts program for toy design and stop-motion. I really enjoyed hand-made props and armature. I like building things using recycled materials and experimenting with different mediums. I like that my puppet/armature is completely imperfect and bit grimy—just like the content of my work, which is a bit smutty and sarcastic. Building small props and sets for the world of Koreangry and physically seeing the work just gives me joy.

What is the most important thing you want to convey with Koreangry?

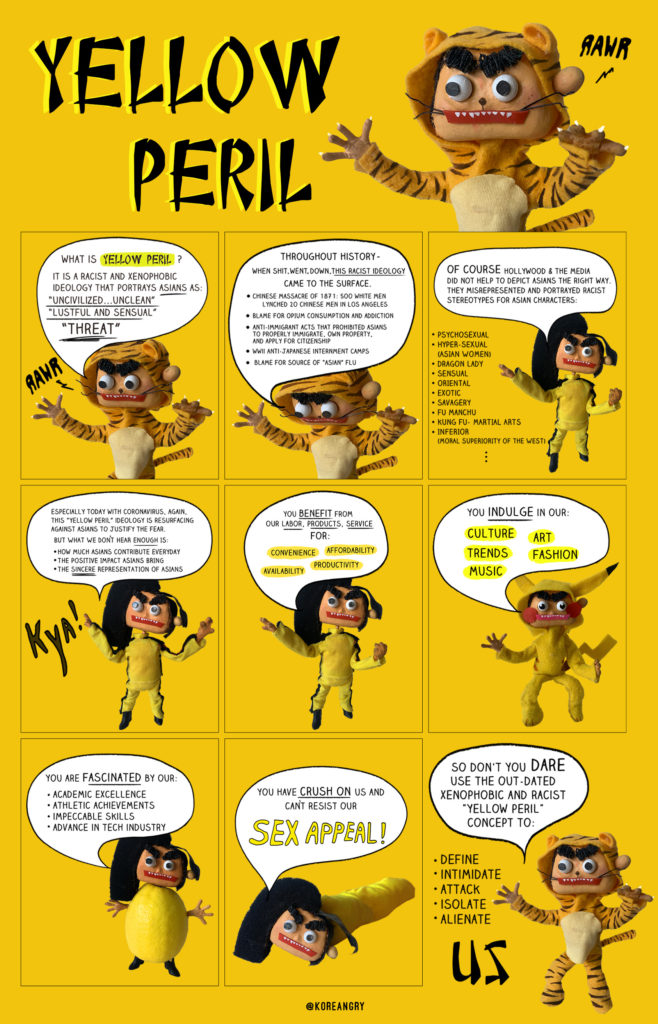

Growing up as an Asian immigrant, I thought it was normal to hear random Asian words or racist slurs thrown in my direction. I wasn’t taught to speak up during those moments because I was told to live quietly and safely. When I became an adult, even in my school and career, I saw myself going along with how people described me, as a stereotypical, one-dimensional Asian woman, and not by how I defined myself. Koreangry is sort of my cute attempt to fight back and undo the outdated narratives within me.

How important do you think it is to incorporate social justice issues in cartoons?

It’s super important because those hard, concrete concepts can be broken down and translated in a visually pleasing and fun way. Representation in comics and cartoons matters because that’s how younger audiences see themselves. The flip side is that there are going to be haters who don’t see your perspectives. It can be challenging emotionally when your work is chewed up by political discourse.

In your ideal world, what would be up next for you?

I want Koreangry to be a show! Last year I held a Kickstarter campaign to self-publish a Koreangry book, and the response was really positive. I would also love to expand to child-friendly content to talk about consent and stereotypes.

Is there anything else you would like to add about the influence your South Korean heritage has had on your career?

As a first-generation immigrant, I struggle a lot with identity. I have lived in the United States for more than half of my life, and it used to feel weird to have pride as a Korean-American. With the surge of interest in Korean cultural influences, I’m focusing on educating myself and others on what Korea is beyond the trends. My last zine issue focused on six months of research into Korean American history over the last 100 years. It has given me a deeper appreciation for my own immigrant history and heritage.

.png)