During the final season of his time-traveling samurai series Samurai Jack, series creator Genndy Tartakovsky started contemplating his next act. He went back to a series of drawings of a caveman and a dinosaur that he had toyed with several years before and brought a series of storyboards to producer Mike Lazzo and the team at Adult Swim.

The untraditional man and beast story became the basis for the series Primal, a show that is by turns touching, heartbreaking, hugely violent and entirely dialog-free.

Tartakovsky, who over the course of his career had overseen the mayhem of the Powerpuff Girls, Dexter’s Laboratory and Samurai Jack, figured his audience was maturing and might be willing to follow him on this new primitive adventure.

“We were seeing that there was a big audience for adult animation. We could finally get to the point where, yeah, we don’t just have to do irreverent comedies. We could kind of do whatever we want,” says Tartakovsky. “We even talked about it. I said, ‘I don’t know how this is going to look on the air,’ but that’s really not my concern.”

Within the realm of adult animation, tastes are expanding and boundaries are being breached about as routinely as some of the creatures dispatched by Primal’s dinosaur, Fang. The expansion of programming streaming services—particularly those without ties to advertising—has opened up the playground to the point where a seriously off-the-wall premise could very easily end up establishing a new animation frontier.

Netflix’s The Midnight Gospel is Duncan Trussell’s podcast brought irreverently and mind-blowingly to life with animation by Pendleton Ward and Jesse Moynihan. Turner’s Final Space went literally into the stratosphere (well, with some help from NASA) to establish its visual universe.

Back on earth, the mantra of Netflix’s coming-of-age comedy Big Mouth, according to Co-Creator and Executive Producer Nick Kroll, is “we give zero fucks” as the humor and the nudity has ratcheted up the animated raunch factor to new levels. Big Mouth will have a new equally foul mouthed playmate joining the slate with Hoops, the saga of a down-and-out basketball coach hoping to take his high school team to glory.

Though new adult animation programming is delving deeper into unconventional origins and spruced-up aesthetics, many of the artists involved cited the influence of much-loved, long- running animated shows while acknowledging that they also want to break free and try new things both visually and thematically.

“I think it’s a really good time to be in animation,” says Devin “DVO” Roth, Art Director on both Final Space and Hoops. “We can be grateful for what shows like The Simpsons, Family Guy and King of the Hill have done, but I don’t think we need to be following those same structures. We need to be exploring new ideas, dynamic angles, interesting ways of cutting, design and color.”

“I’m hearing about people from the experimental animation world who are getting meetings in the world of TV to develop stuff, and I find that to be pretty promising,” adds Jesse Moynihan, Art Director on The Midnight Gospel and a writer and storyboard artist on Ward’s series, Adventure Time. “If Midnight Gospel does well and people like it, it’s going to give people like myself the opportunity to keep developing more thematically dense and adult kinds of ideas in animation.”

THE FAMILY GOES NUCLEAR

Traditionally, everything—live action or animated—started with mom, dad and the kids. A nuclear family—the more dysfunctional, the better—has been the basis of countless animated series. The Flintstones may have lived in Bedrock, but they never shared a bed. The world of the future envisioned by The Jetsons now comes across as anything but futuristic. As the 1980s came to a close, a quirkily-drawn family wandered out of The Tracey Ullman Show and into history, changing the game forever.

It has now been more than 30 years since Homer, Lisa, Bart et al. planted their flag as an animated family sitcom populated with a tribe of anti-heroes that wasn’t afraid to go to some dark places. A decade later, Seth McFarlane unleashed the raunchier and racier antics of the Griffin family of Family Guy. The Belchers of Bob’s Burgers and the Hills (King of the Hill) inched ever edgier and by the time genius inventor Rick moved in and started taking over the education of his dim-bulb grandson Morty, nobody blinked.

Animated series still revolve around families, but in this new frontier, the unit has taken on new forms. Final Space’s Gary Goodspeed roams the galaxy with a ragtag band of fellow adventurers and a planet- destroying puffball named Mooncake. The “family” of Hoops is a coach and his students. “Breaking the whole family sitcom structure, that’s something I like,” says DVO who characterizes the series as a cross between The Mighty Ducks and The Bad News Bears. “What’s great about Hoops, I think you’re going to see that it has taken an approach of blending in the ideas of teen animation and adults programming. You’re going to be seeing over the next five to 10 years a big change in what is considered adult animation.”

“What I was trying to do was make this team and the coach a weird version of a family,” says Hoops Creator Ben Hoffman. “My junior high basketball coach was kind of a crazy person. [He] made his living scalping tickets…let us not run laps if we brought him candy.”

You want dysfunction? How about a washed-up Hollywood stallion trying to come to terms with life as a has-been? BoJack Horseman’s creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg mined the isolation he experienced when he first came to Hollywood and put his artistic vision in the hands of artist Lisa Hanawalt.

“I do think the drive to support more creator-driven content is going to help individualize a lot of animation styles,” says Background Artist Liza Epps who worked on BoJack and Final Space. “It influences everything from backgrounds to character designs to how the characters think and act.”

Some of these characters could probably use a family. Whether you’re considering Clancy, The Midnight Gospel’s galaxy-hopping interviewer; Spear whose family is wiped out in Primal’s opening episode; or the self-loathing BoJack Horseman, you have a trio of protagonists who either spend great periods of time alone or are seeking some sort of connection, human or otherwise.

Any trends away from families and toward lonely or isolated characters is a reflection of real life, says Mike Mayfield, Supervising Director of The Midnight Gospel and Big Mouth.

“Adult animation, at least in the U.S. has done the nuclear family really well, but there’s a lot of other ground that these stories can cover,” he says. “The way human beings act and hang out and live and have inter-personal relationships has always had a ton of different shades and combinations and varieties. Animation would also reflect that, so you’re seeing different types of structures that aren’t even necessarily a family—a friend group or co-workers or all those different types of inter-personal formulas.”

BoJack took plenty of genre-bending risks. Supervising Director Mike Hollingsworth harkens back to the third episode of Season 1 in which former child star Sarah Lynn throws a party, trashes BoJack’s house and is seen flicking matches at a torched ottoman. Series creator Bob Waksberg asked if the burned ottoman could stay in place through the season.

“Reflexively, I replied, ‘No, it has to go back to how it was. In cartoons at the end of every episode, everything goes back to default,’” says Hollingsworth. “Raphael countered, ‘Well—what if it doesn’t?’ The line producer and I looked at each other with fear in our eyes. What Pandora’s Box was being opened here? Fast forward through six seasons and that whole furniture set was destroyed and replaced three times. His bed was smashed, and for a whole season there was a Tesla parked in his swimming pool. That means we had to draw an upended Tesla, from many angles, into all our ‘stock backgrounds.’

A NEW AESTHETIC

Budgets will always be tight and schedules will be crunched, but in the ever-changing realm of adult animation, one thing that artists working on these shows say will not—or should not—be compromised is a show’s look. The aesthetic of a lowbrow show can be correspondingly lowbrow if the aim is laughs, but that won’t fly as easily if your show is treading new ground. Eleanor Michalka, Lead Background Designer for The Midnight Gospel, had no difficulty embracing the ever- shifting needs of the show’s visual demands. A long time follower of Trussell’s podcast and an admirer of Ward and Moynihan, Michalka said she approached Gospel “with reverence and determined to produce the most beautiful work possible.”

“Maybe it’s our own cultural self- image improving,” Michalka says. “I’ve always seen artists pour themselves into something and they get kind of disappointed when they’re told. ‘Oh that’s too nice. Make it worse.’ On another level, it’s not about the mindless consumption of beautiful images or ugly images. It’s about knowing why you’re consuming that image in the first place.”

“A lot of the background concepts I would do were very light-heavy in mood and tone, so I enjoyed creating those worlds …”—Final Space Background Artist Liza Epps

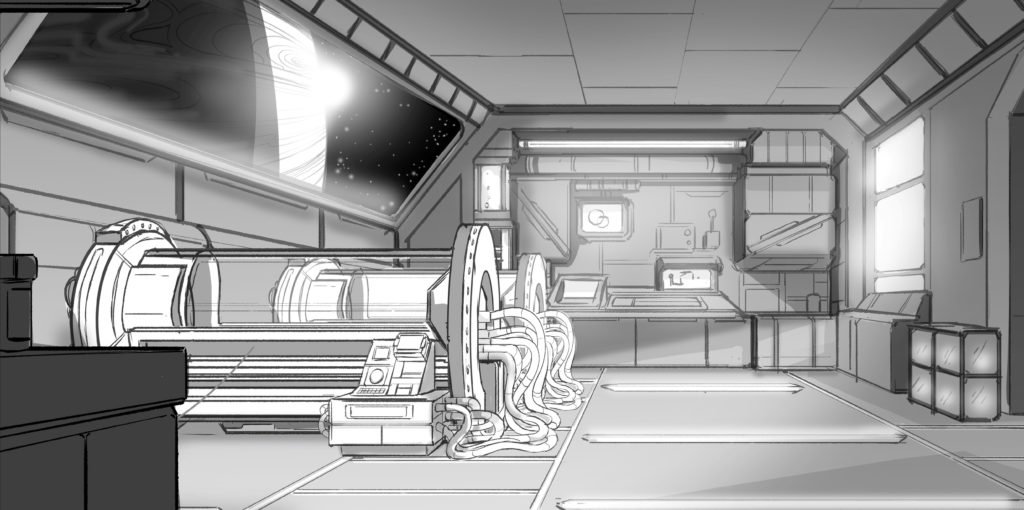

In creating the aesthetic vision of Final Space, creator Olan Rogers felt the sky was limitless.

“You look at the shots that NASA takes with their telescopes, these beautiful, sprawling space shots and I was like, ‘I want to put that in the show,’” recalls Rogers. “The first pass was like a peek of space and I was like, ‘No, no, no…I want real space. I want to figure out how to incorporate actual NASA images with 2D in the show.’ Once we did that, it really kind of gave the show a different aesthetic.”

Final Space Art Director DVO combed through the NASA library and started building star fields. Instead of the usual dots in the sky one sees in a traditional space program (live action or animated), Final Space turned every flight into the equivalent of a graphic novel. According to background designer Epps, the line work and the heavy use of black was used to help achieve this look. She recalls doing a black shadow pass to give the backgrounds an inky feeling reminiscent of graphic novels or comic books.

As the series traveled to different worlds, Epps recalls drawing visual inspiration from the art of Syd Mead, and films like Blade Runner, 2001 and Indiana Jones.

“A lot of the background concepts I would do were very light-heavy in mood and tone, so I enjoyed creating those worlds,’ Epps says.

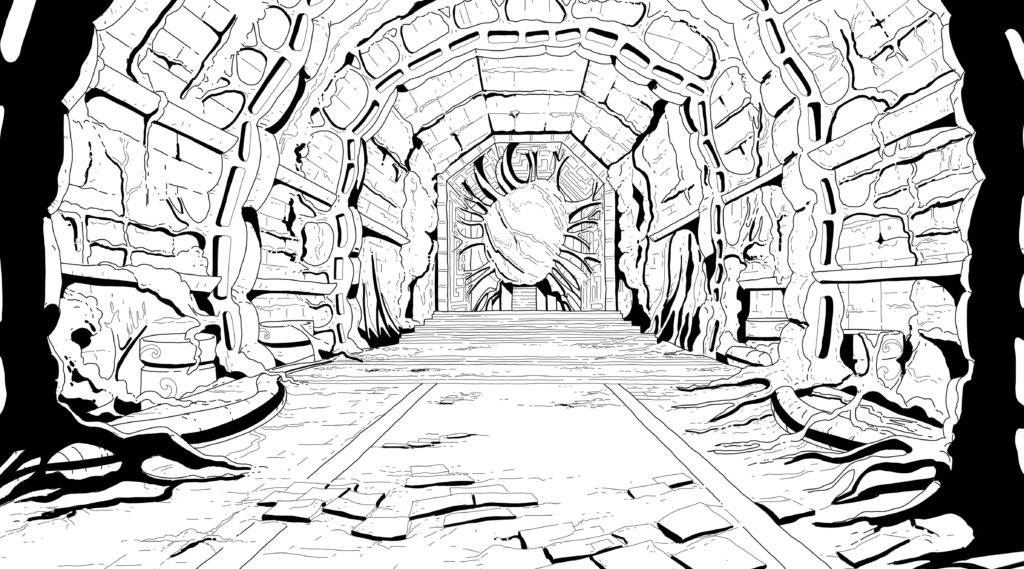

Primal’s aesthetic includes plenty of nods to the visual styles of graphic novel and comic book artists. Tartakovsky referenced the art of science fiction cartoonist Frank Frazetta and the Conan comics of Robert E. Howard. Tartakovsky and Art Director Scott Wills originally gravitated toward 1970s era sci-fi art before moving in a different direction as the storytelling began to mature. The rules of the series included no blue sky, no green grass. Every color had to have a meaning.

“Because there’s no dialog, the animation had to do a lot more work,” Tartakovsky says. “Having the studio and the young animators really put in their all took the animation to a level that I pretty much have not done this consistently in television.” A show like Primal doesn’t figure to be an outlier for long. Industry watchers say that as 2D design and CG animation continue to meld in eye-popping ways, narrative will also up its game and viewers can expect deeper and darker stories. Meanwhile, the pipeline for new and creative concepts in adult animation won’t be clogging up any time soon. Buzz is building around programs like Titmouse’s Q-Force, Sony Pictures Animation’s Hungry Ghosts (based on the graphic novels of Anthony Bourdain) and Sony and Netflix’s Agent King, which takes its inspiration from Elvis Presley’s childhood dreams of being a superhero.