Welcome to our story. Thank you for engaging. Keep reading and we will regale you with a tale of interactivity and how the once novel concept of the “choose your own adventure” has become a feature of several TV programs geared toward animation lovers of all ages…

…Or if you CLICK HERE, you can fight a dragon, confront an evil sorceress, rescue the kingdom and get treasure beyond your wildest dreams. Read on or fight. You have ten seconds to decide.

OK, so we were kidding about the dragon and the riches. But you were just a little bit tempted by that second option, no? Who among us, whether intensely gaming or passively viewing our favorite episodic, isn’t intrigued by the proverbial fork in the road and the chance of being the one to determine our hero’s next steps? Who doesn’t love options?

“What can we do that requires it to be interactive and not just, ‘Here’s a typical story we would tell with a couple of token branching choices, but really it amounts to a normal episode?’”—Writer Brandon Sawyer

That is, of course, a key reason why many of the men and women who have worked on programs with an interactive component find the experience as exciting as the viewers who actually get to engage with it.

“It opens up a whole door of possibilities for the building of worlds, the building of franchises,” says Dan Forgione, a veteran director and storyboard artist on such titles as The Boss Baby, The Adventures of Puss in Boots and Randy Cunningham: 9th Grade Ninja. “You can be building and extending stories beyond just time limit with infinite possibilities. Of course, there would have to be infinite money and budget. Somebody would have to pay for that, but from a storytelling standpoint, it’s kind of a challenge.”

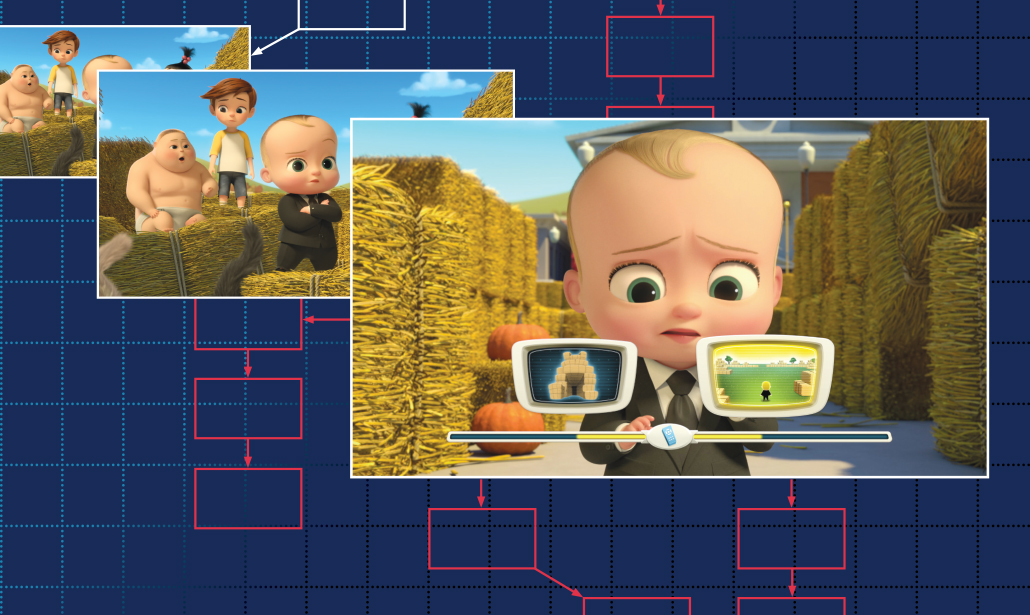

Forgione was one of three directors in charge of a team for the special event Boss Baby: Get That Baby! which offers its viewer 16 different endings. Three years ago, he worked on another DreamWorks interactive project, Puss in Book: Trapped in an Epic Tale, when the format was still largely in its infancy. Now, new programs and established franchises are jumping into the CYOA pool with equal gusto.

Producers of interactive episodes—which are almost always presented as special episodes of an established show—emphasize that the CYOA component is a new spin, not a gimmick. As Carla Engenbrecht, Director of Product Innovation, Interactive at Netflix insists: “We are storytellers first and foremost.”

“We’re really excited to see what kinds of stories creators want to tell and what our members want to watch,” Engelbrech says. “Now, we can share interactive rom-coms, horror, mysteries… it’s really up to our creators and their imaginations.”

The Boss Baby adventure allows viewers to follow a story that serves as a training exercise determining their ultimate placement in Baby Corp. In Carmen Sandiego: To Steal or Not to Steal, the viewer guides the titular master thief through a heist while trying to figure out how to save her friends, as new choices pop up every few minutes. Skewing decidedly older, Batman: Death in the Family puts the fate of Robin literally in the player’s hands when experienced on Blu-Ray. And it’s not just animation. Netflix has recently produced You vs. Wild, an interactive episode of the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, which was considered every bit a game-changer.

Going back further, animation lovers of a certain age can harken back to the early 1980s when gamers lined up outside of arcades (remember those?) to have a go at the newly released game Dragon’s Lair. With animation by ex-Disney maven Don Bluth, the game put the player at the controls of an animated movie.

Interactive animation has come a long way in the ensuing decades. These days the choices are more numerous, the integration more seamless and the execution more sophisticated. Building an interactive program still takes a ton of labor and strategizing and the technical prowess of proprietary software that helps sync everything up and keep all of the decision points under control. Of great help is Netflix’s Branch Manager software, developed for Bandersnatch, which helps creators keep track of their nonlinear story by allowing the input of video clips, storyboard and choice points. The writers who worked The Boss Baby and Carmen Sandiego specials recall endless numbers of Post-it notes on storyboards trying to help the team keep each branch of the tree distinct.

“It was quite a web and we were spinning a lot of plates,” says Duane Capizzi, co-executive producer of To Steal or not to Steal, “but a key thing honestly was having someone on the team who knew gaming and who had familiarity with how to design games. Producer Sam Nisson was our secret weapon. He was able to chart out the branches in a huge tree-like diagram with all these figurative branches. That was really the key to being able to see how it all played out.”

In many of the recent programs, the decision to build an interactive episode originated with the studio. With more than 10 specials, Netflix has started to make the practice mainstream. For a property like Carmen Sandiego, which originated in gaming, an interactive adventure was a natural choice, according to Capizzi.

But the “make it interactive” directive, while replete with creative challenges, is also a daunting ask when you’re attempting it for the first time. Boss Baby writer Brandon Sawyer recalls being terrified when the idea was broached. The first question to be answered—why?

“What’s the justification on our show?” Sawyer asks. “Why interactive? How can we use this format in the world of this show we had been making for—at that point—30 episodes? What can we do that requires [a show] to be interactive and not just, ‘Here’s a typical story we would tell with a couple of token branching choices, but really it amounts to a normal episode?’”

Sawyer’s first idea for Get That Baby was to have the series’ villains return and hatch a plot to kill Boss Baby. While that plot didn’t fly, the villain reunion was incorporated and the plot became a training simulation enabling the viewer to determine what division of Baby Corp. he or she would be best suited for. A choice may lead to a dead end or a redo, but no decision is ultimately the wrong one and players could go back and try for a different outcome (there are 16 to choose from).

“One of the speed bumps I encountered was just how easy it was to lose track of similarities between certain sections,” agreed Boss Baby’s Forgione. “Because it was nonlinear, there were some cases where some parts would jump further along. It was interesting to see how three different teams could come up with similar stock choices or even just compositions for very similar moments at different points in the story.”

Each of the episode’s three directors oversaw three storyboard artists, and divvyed up the work into thirds. Essentially that meant the entire staff that worked on Get That Baby created enough content for three episodes. The choices along the way even included a 2D 16-bit negotiated fighting game complete with diminishing life bars.

The Carmen Sandiego team wrestled with whether their special would be a stand-alone episode or whether it needed to fit into the structure of the series. To Steal or Not to Steal became a special episode, but the team had to deliver it while simultaneously working on Season 2, which meant the need for additional manpower. Once it was determined that the interactive episode would be a stand-alone special, that opened up possibilities.

“We were like, ‘Oh, so we can do dream sequences,’” says Capizzi. “Interactive storytelling is about choosing. There are forks in the road and you choose your own approach to problem solving. We got really excited about the opportunity to do dance numbers and dream sequences. I don’t think any dream sequences made it in, but two dance numbers did. It was about as close as we have come so far to doing a musical episode.”

The tone is darker and the stakes higher in Warner Brothers’ Batman: Death in the Family. Writer-Director Brandon Vietti was anxious to jump into the interactive format and he found a natural match when it was decided that Death in the Family would take its inspiration from a 1988 comic book story that had left the fate of Jason Todd—the second Robin—in the hands of readers. Shortly after the character was introduced, comic book creators gave out a toll-free number and invited readers to call in and vote whether Todd should live or die.

“The interesting part of interactivity is creating stories that play out in ways that may not follow what you think will happen.”—Brandon Vietti

Spoiler alert: They voted that Robin should bite the dust which, three decades later, became a sequence in Death in the Family as well. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

“Different writers come along as time passes and people imagine new ways to bring a character back,” says Vietti, who has also been a storyboard artist on multiple DC Universe series. “It made this particular problem so interesting to go back into because you don’t know what is going to happen after you make a choice. The interesting part of interactivity is creating stories that play out in ways that may not follow what you think will happen.”

Death in the Family gives the viewer six decisions which lead to seven different endings. The death of Robin storyline may have a certain familiarity to viewers who have been following the animated adventures of the Caped Crusader. Vietti was able to repurpose and reuse extensive footage from his own 2010 film Batman: Under the Red Hood within Death in the Family.

The original film needed editing to allow it to sync up. Mouth movements had to be recalibrated for new dialog. The two films didn’t share the same animation team so character and background looks had to be consistent.

“From the writing phase, I had to have the old movie open on my desktop and be writing down time code and editing the movie while I was writing it,” Vietti says.

“Thinking about the end as I was coming up with the beginning was the biggest challenge of all. Everybody had to go back and study what had been done before to try to connect with it, myself included.”

The Batman adventure is for mature audiences. There are fewer overall choices which, Vietti says, is deliberate since he wanted his end product to feel more like a story and less like a game.

Given the way the technology is evolving, Vietti sees future watchers interacting in subtle and more sophisticated ways. If a smart watch can help gauge heartbeats and moods, the same device might be able to help a program determine your choice. So if you are experiencing an adventure as Batman, for example, the biorhythms you express whether looking at a corpse, a weapon, a computer terminal or a newspaper clipping may help the program decide which story path you choose.

“We’re talking about harnessing technology to create stories that are interactive in ways we can’t even imagine,” Vietti says. “I’m hoping we get started on this sooner rather than later.”