When Lisa Kollins went to her high school homecoming dance with Tim Yoon, she had no idea that years later she would reach out to him to help make dozens of children’s dreams come true.

In her eighth year as a volunteer program specialist and cabin counselor at Camp Sunrise, an Ohio camp for children impacted by HIV/AIDs, she thought it would be fun to ask the kids what they would look like and how they would make the world better as superheroes. Then, on the last day of camp, they would be surprised with posters of themselves as those characters.

In need of more than 100 artists, she remembered that her long-ago date now worked in the animation industry. She sent Yoon a message, and soon he responded with dozens of names.

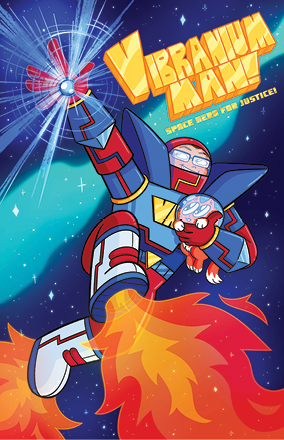

Among them were TAG members, including Jeremy Polgar. Currently directing and show-running music videos, Polgar says: “It was a really strong, simple idea. It was an easy thing to say yes to.”

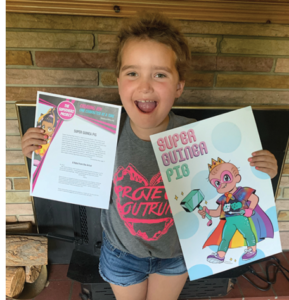

The result was a slideshow on the last day of camp, where Kollins realized “how powerful it was [for the kids] to see themselves reflected in such a joyful way, with such strength.”

Kollins considered how she could turn the project into an ongoing, sustainable program.

The ensuing Superhero Project kicked off in late 2017 with patients at a Cleveland children’s hospital. Soon word spread and individual families and other organizations reached out.

“I got my first prompt and I was like, oh, this is a creative, fun, challenging assignment.” He was able to work the girl’s ten dogs into the poster, but he couldn’t figure out how to include her cage that captured bad guys—so he had Kollins add a note explaining that a miniature cage, that expanded when needed, was hidden in a pocket.

Each poster begins with an in-person or video interview. First, kids are asked to describe themselves. Next, they describe who they want to be as a superhero. (If they’re nonverbal, parents, siblings, and other loved ones provide this information.) The descriptions that are then sent to artists can get elaborate, according to Polgar.

“You really have to step outside of yourself and what it is you feel comfortable drawing,” Polgar says. “That’s what’s fun about this assignment. And you’re giving [kids] a gift of letting them see their own imagination. You really want to show them empowered in the way they want to feel empowered.”

Polgar’s enthusiasm attracted other TAG members like Danny Ducker, a storyboard artist on Amphibia and an Executive Board member.

“It’s so different from anything I would draw for myself or draw for work,” she says. “It’s never a moment of frustration, but it is a moment of, oh God, how am I going to do this? I really want to make this kid happy.” For example, “they want a rainbow cape, but they also want rainbow hair. As an artist, let’s figure out a way to make that look like it makes sense and doesn’t blind anybody.”

“Kids are honestly the most fun art directors!” adds Julia Srednicki, another TAG artist Polgar recruited. A character designer at Netflix, she says that the trick is taking the child’s lead while making sure you’re creating something original. “This 4-year-old really wanted to be the Hulk—but I tried my best to pay attention to and emphasize the specifics he mentioned, like ‘big green feet’ and ‘lots of muscles’ to be sure it wasn’t just a generic Hulk… My hope was that the child would instantly recognize himself as his own unique hero.”

Each artist is drawn to the project for different reasons. Srednicki felt it was “a perfect chance to put our everyday work skills to use to bring some joy to a kid going through a tough time—and in a way that specifically reflects their own creativity and admirable qualities right back at them.”

Those admirable qualities are what appeal to Ducker. When asked about their superpower, “some [kids] are like, ‘I go to other kids like me and make them feel better.’ I just can’t imagine being that young and trying to process the position you’re in. It’s very touching that their response is wanting… to make other people feel loved.”

The interviews serve a deeper purpose than simply aiding in the creation of the posters. One mom of a child with special needs explained to Kollins, “We’re always asked to talk about the things our kid can’t do… to explain what the deficiencies are.”

“[The Superhero Project] really flips that on its head,” Kollins says. “We’re asking them to tell us how their child makes the world better every day.”

Kollins says she’s surprised at the effect a single poster can make: “[Families have] reported back that their kids, after seeing their superhero and going through this process, have more self-confidence. That they seem more comfortable with their bodies and with their body differences because they’re being celebrated. Being in a wheelchair is one thing. Seeing yourself in a rocket wheelchair shooting across the sky is something totally different.”

.png)