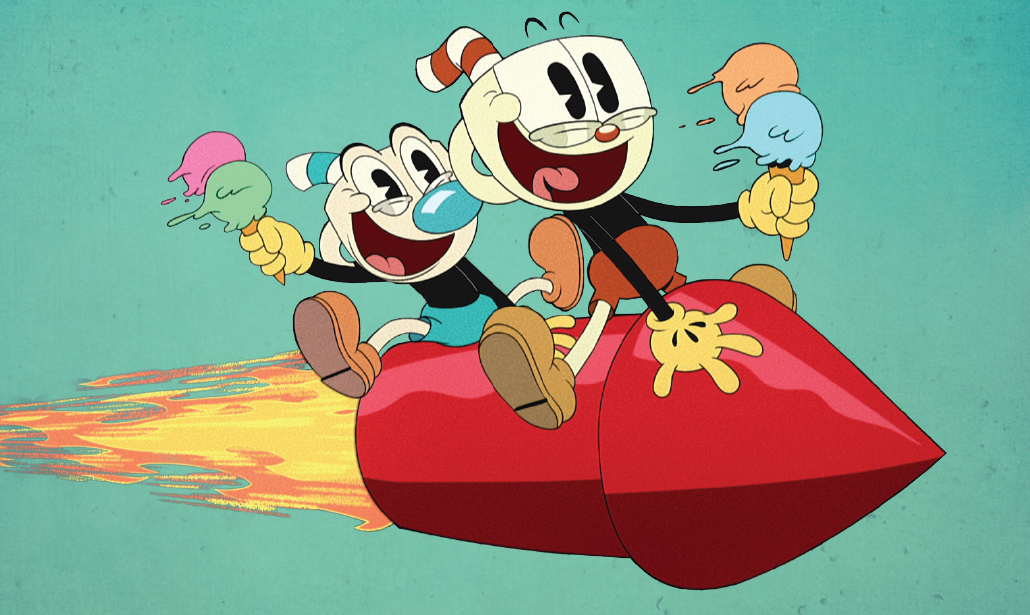

When Cuphead came out in 2017, it wasn’t your typical run-and-gun video game. The style was inspired by rubber hose animation and surrealist storylines from the Golden Age of Walt Disney and Fleischer Studios cartoons. The effect created by Chad and Jared Moldenhauer looked so authentic to the time period that when they initially showed footage of the game, people asked where they licensed the characters from. So it didn’t come as a complete surprise when Netflix commissioned an animated TV series based on the award-winning game called The Cuphead Show!, which premiered last month.

But a game is after all a game, with a limited narrative and no clear story plots. The creative team’s first challenge was to develop a solid story arc and infuse personalities into the various characters.

“We [had] to reverse engineer personalities into these characters and find meaning. How do we make their personalities funny? Where do we create friction?” says Executive Producer and Showrunner Dave Wasson, who worked together with Co-Executive Producer and Writer Cosmo Segurson. He and Segurson mined the storybook sequence at the beginning of the game for ideas and found inspiration in an image of Cuphead sitting at a craps table having the time of his life, while Mugman hangs on the edge of the table, a look of palpable fear on his face.

“We took those bread crumbs and it was like, okay, so we know Cuphead’s impulsive and reckless and doesn’t think about consequences. What pairs well with that? Somebody who’s more grounded, who is maybe a little more cautious,” says Wasson. This dynamic relationship between Cuphead and Mugman—combined with the grouchy Elder Kettle, Ms. Chalice, the Devil, and more—created the perfect comedy engine for the story.

Given the target family audience, Wasson and Segurson wondered if featuring the Devil would be too controversial, but they pushed for the character’s inclusion. “In order to have strong heroes, you’ve got to have a great villain. And what better villain than the Devil himself?” asks Wasson. The story team devised a premise where Cuphead is a fly in the Devil’s ointment, and for the first time ever, the Devil is frustrated.

“We all felt like frustrated characters can be really fun to play with as a character trait. We pushed it even further—he’s really vain and very self-aware. I think he’s definitely the most complicated character in the series,” says Segurson.

Bygone Eras & Modern Storytelling

“Every morning we would have a cartoon kickoff where we’d watch at least three classic cartoons, as well as maybe some live-action shorts from the period,” says Segurson. “I think everyone was ready to just fully dive into this kind of 1930s-style humor and animation and music.” Inspiration was drawn from other eras and sources including a myriad of historic references from Popeye to the Silly Symphony series, the vocal rhythms of Frank Capra films to the comedic timing of The Three Stooges.

Where they did veer from some of the more vintage animation influences was in the story, opting for a character-driven comedy. “Audiences [then] weren’t as sophisticated as audiences are now, and so just to see a character moving in a silly cycle was enough to entertain someone. It was like seeing a magic trick. [Now] almost a hundred years later, people have seen more sophisticated acting, more sophisticated joke telling,” notes Wasson.

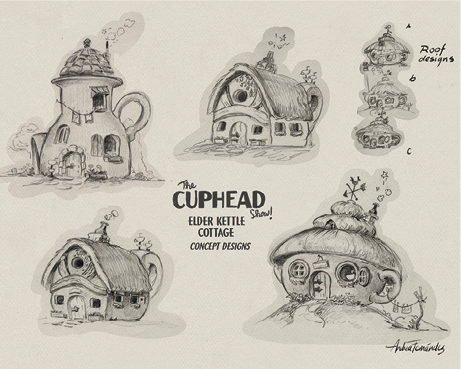

Art Director Andrea Fernández remembers one of her first meetings while working on Cuphead. Hundreds of characters were pinned on a wall, and they started discussing which characters to make episodes out of. She was included in story conversations from the beginning, so she could start envisioning the world and, more importantly, how to accomplish it technically. She credits this collaborative process with helping to pull off the intricacies of the show, wrangling the multitude of influences and ideas into workable, budget-conscious solutions.

“The hardest part was to take everyone’s hopes and dreams, and then put guardrails around it and really make decisions about how we could actually make a show that looks like this in the timeline given and with the resources we had,” says Fernández. They had to examine every creative decision and be deliberate in their choices. The backgrounds were incredibly intricate, intentional, and detailed.

“There was just a lot of strategy,” says Wasson. “If we’re going to have one really big adventure episode where [we had] lots of new locations, then we would try to have an episode right before that mostly took place in the cottage…[and] easier for the background team.” This trade-off manifested in smaller, more character-driven stories followed by episodes with larger scale adventures.

“This isn’t like modern shows where you can just move every layer around and it’s relatively flat, and I’m going to get you a new background in about two to three hours,” says Fernández. “Each background took up to 16 hours to paint.”

Adapting to the Past

Aside from sometimes viewing backgrounds as a quasi-live-action set, the storyboard artists had to adapt their techniques to account for the time period, eschewing anime shortcuts and dynamic angles that didn’t exist in the 1930s. Instead, storyboard artists like Megan Boyd focused on the gags, strong staging, and hitting cinematic moments where they count. “It was a fun challenge of picking moments to really highlight the animation,” she says.

The storyboard team and directors started with denser outlines with some dialogue written, a few pre-visualization drawings for each episode, and references such as textiles or architecture from the period. Each team would then add their own jokes and ideas, encouraged to get creative and sometimes pitching wild storylines. “I think all the boarders went crazy at first,” jokes Boyd.

The other key consideration for the storyboard artists? Music! “So much of that 1930’s jazz has such great beats and rhythms that I can listen to it with my eyes closed and just see characters moving to it,” says Wasson. They wanted to emulate this synergistic relationship between movement and sound, and enlisted the help of Ego Plum to compose the music for the series. For the more music-driven episode sequences, Wasson and Segurson collaborated on original songs, with everyone on the team immersing themselves in music from the era.

For the finale episode of Season 1, “In Charm’s Way,” Boyd choreographed a tap-dancing number for Ms. Chalice as she takes the boys on a joyride through town and dances on cars. “I spent a long time watching old-timey tap-dancing videos, trying to get the era in my mindset, so it felt authentic,” she says. “It’s just a really fun challenge making something visually flow with music.”

For these self-proclaimed animation nerds, an opportunity to share their appreciation for the 1930’s rubber-hose style was a dream come true. “It was kind of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity project,” says Fernández. Adds Segurson: “It completely embraces the magic of animation in a way that I haven’t been able to work on in another series before. And maybe we’re going to bring it back, where no matter how old you are, you can find humor and you can find the wonder of the animation itself, all in one package.”