INTO THE WILD

Open Season

Sony Pictures Animation

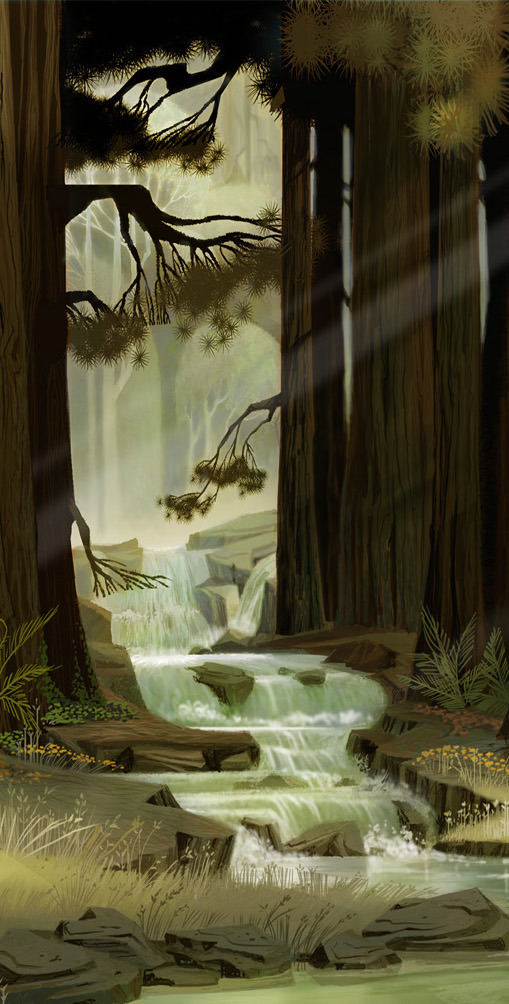

Landscape: Forest

Production Designer: Michael Humphries

In Open Season, Sony Pictures’ first animated feature film, Timberline National Forest is the fictional backdrop for the comedic adventures of a domesticated grizzly bear named Boog, who’s been returned to the wild just before hunting season. Its unique but familiar look was created by Production Designer Michael Humphries.

Humphries recalls that when he met with the film’s directors, he was asked, “Do you like Eyvind Earle?” Not only is Earle—the man behind Sleeping Beauty’s aesthetic—one of his artistic inspirations, but he had just finished working on Home on the Range based on Earle’s style. He was hired immediately and given artistic freedom as long as he kept to Earle’s spirit. To do this, Humphries says he tried to put himself in the head of Earle while he worked.

A large part of the visual development process involved doing an enormous amount of research. Humphries and his colleagues flew up to the Muir Woods in Northern California. “We spent an entire day just photographing the forest and sketching,” he says. They observed the shapes, taking note of anything that would give them a sense of the environment within a forest. Very early on in his process, he started the design in a traditional way with acrylic paint on paper. “Once I got the look that I wanted, then I translated everything into Photoshop so I could share all of the files with the other artists,” he says.

Humphries designed several trees, many of which were based on pine trees and their triangular shape, playing around with different versions and making his own interpretations. “You translate the real tree into a graphic design,” he says, “and then, when you build the CGI model, you can also do different positions of the tree [and] different heights and sizes.” He adds that if they’re placed properly in the environment, you don’t really notice that it’s the same tree over and over again.

The big challenge was to make a 2D style work in a 3D CGI movie. All of the CGI elements, he explains, make everything look extremely real, yet the idea was to continuously maintain the overall 2D look. To achieve this, he would make brushes that were 2D flat shapes and incorporate their brushstrokes in the distant mountains and trees. Anything in the distance was kept almost entirely in 2D, “and then we’d put 3D elements in front of that based on what we needed to do,” he says. Finding a balance was challenging, and he had to remind the CG artists not to let everything get super real or over-rendered, but to rather try to keep the imaginative cartoon feel.

It was also essential to maintain the continuity of the style throughout. In terms of landscape painting, he says, a lot of it has to do with overlapping shapes,

creating a scale and an atmospheric perspective, and looking at how you can push something back in terms of color. He points out that color is an important design element, one that is not used arbitrarily. Like music, color evokes an emotional reaction in the audience and for that reason, he adds, “We always control the palette as much as we can.”

Then, of course, there is the issue of characters. Humphries worked with Character Designer Carter Goodrich, experimenting with placing the characters in the environment as part of the visual development process. “That way we could see how the characters married into the scene and the overall environment,” ensuring that the landscape felt organic to the emotional arc of the characters and story.

TRAVEL TIP

Timberline National Forest may be fictional, but its inspirations are real. Using Open Season as a guide for your summer getaway, head to the nearest national park forest and discover for yourself the unique shapes and colors to be found in our woodland landscapes.

ISLAND TIME

Moana

Walt Disney Animation Studios

Landscape: Pacific Island

Production Designer: Ian Gooding

Set on the fictional island of Motunui, Moana captures the lush beauty of the Pacific Islands and the ocean that surrounds them. Originally from Jamaica, the film’s Production Designer Ian Gooding thought that being from a small island in the tropics would be beneficial to his job. “But it turned out to be helpful in the opposite direction, which was that I wanted it to not look like it could be in Jamaica,” he says.

Gooding points out that the islands in the Pacific are formed differently due to the nature of their volcanic eruptions. As a result, they tend to have reefs going all the way around which give them “a very specific look and a very specific kind of wave action.” Because of this, he learned about how islands differ geologically so that he and his crew would be able to highlight these differences.

The ocean is an integral part of the film, and much of the action takes place on the water as Moana sets out on her voyage. At the start, Gooding and his team “looked into a lot of … methods of stylizing the water so that it looked like tattoos and all sorts of interesting things,” he says. But ultimately, they felt it would be better to try and capture what was so spectacular about these places in real life. One example is the way that light interacts with clear water and the white coral sand beneath it, or what he calls “the spectacular dance of light.”

“[Motunui] was inspired by the three islands that were where anthropologists believe initial [Polynesian] migrations ended: Tonga, Fiji, and Samoa”—Ian Gooding

Gooding explains that the whole movie got a color script to show how color would be used in any given sequence. When the action took place far out to sea, the ocean was given deep ultramarine colors as opposed to the shades of turquoise you get closer to the shore where the white sand is visible beneath. The ocean itself is a character in the film, choosing Moana to return the heart to the mythical mother island, Te Fiti. When the ocean became a sentient creature, the artists reserved a very specific blue-green color for those scenes. The intention was to help cue the audience that the “ocean is going to do something magical now,” says Gooding. At the same time the challenge was not to make it so obvious that it would take viewers out of the movie.

The fictional Motunui, says Gooding, “was inspired by the three islands that were where anthropologists believe initial [Polynesian] migrations ended: Tonga, Fiji, and Samoa.” For research, he and his team visited Samoa, Bora Bora, Tetiaroa Atoll, and the tiny island of Manana, to drink in the experience of the quieter pace of life and immerse themselves in the ancient culture. When Gooding first landed in Samoa, he was surprised to find it looked exactly like Jamaica. He learned the flora was similar because of the way people had moved plants around the world over time.

A botanist, Frank Murphy—who is married to Hinano Murphy, the film’s Tahitian cultural consultant on the Oceanic Story Trust—helped map out which plants would have been on the islands 2,000 years ago, information gleaned from pollen samples taken from drill cores. Gooding says that in a flashback scene they were able to show the island before the Polynesians arrived and how the vegetation differed. That said, the plants at that time had chiefly yellow and white flowers, so they did take creative license in order to have a broader range of colors.

Gooding points out that while the rest of the world might find it confining to live on a small island, “the Polynesians see the ocean … like connective tissue, the thing that joins the islands together, as opposed to the thing that separates them.” He adds that they “were navigating the world’s largest ocean reliably, hundreds of years before the Vikings.” This was why it felt so important to depict the ocean with such accuracy, to convey the courage and strength required to venture out across its vast waters.

TRAVEL TIP

The world of Moana is enticing with its idyllic island setting. While Gooding found Bora Bora gorgeous, the holiday splurge he’d recommend for those with infinite funds is the exclusive, pristine Tetiaroa Atoll.

CITY GETAWAY

Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted

DreamWorks Animation

Production Designer: Kendal Cronkhite

Landscape: European Cities

In the third installment of the Madagascar franchise, the zoo animals leave Africa for New York via a sweeping tour of Europe including stops in Monte Carlo, Rome, Switzerland, and London. Production Designer Kendal Cronkhite calls it “a huge travel film.”

This meant a 10-day research trip to shoot reference material, with the first stop being Monte Carlo. “When the main characters [arrive] up out of the water, that’s where … we get a view of the whole of Monte Carlo,” Cronkhite says, describing how she and her colleagues went out on a dock that extended far into the water. From there they were able to get a complete view of the Bay of Monte Carlo, a reference they used often.

Because this was the third Madagascar film, the design for the “cartoony stylized look” was already locked in. “Although for each one, we tried to adjust it slightly to be even better,” says Cronkhite. “There’s a lot more of a hand-drawn line in Madagascar 3.”

“Because [the animals] were traveling so much and so quickly over the course of the film, it was super important for our audience to get, ‘Okay, we’re here now.” —Kendal Cronkhite

When it came to the cityscapes, they were looking for authenticity. Along with the team’s reference footage, Cronkhite says that travel and Grand Prix posters from the 1950s and ‘60s were a source of inspiration. They were also influenced and inspired by the work of Japanese illustrator Tadahiro Uesugi because they loved his beautiful cityscapes, and by illustrator Miroslav Šašek who created the This is… series of books featuring cities around the world.

While researching in Monte Carlo “we knew there was going to be this rooftop chase,” says Cronkhite, revealing that she and her team were actually allowed up onto the roof of the famous casino where not many people have access. “We walked all over that thing. It was its own landscape, and it was really fascinating,” she says. They used what they found there pretty much verbatim in the movie. In fact, the glass skylight that the animals crash through and the casino room they fall into below is based closely on reality.

One of the hardest parts of capturing the cities, Cronkhite shares, was the establishing shots. “Because [the animals] were traveling so much and so quickly over the course of the film, it was super important for our audience to get, ‘Okay, we’re here now,’” she says. It was a challenge to find dramatic establishing shots that were unique but also completely recognizable. With London, she explains they did the establishing shot from the London Eye. “Luckily, being there helped because we could move to those places, shoot lots of photos and video, and try to get [what we needed],” she says.

Another challenge was just how much had to be designed with so many different locations and chase scenes. There was also the issue of how different the light is in each of the cities. “Monte Carlo is so crisp, white and blue,” says Cronkhite. Everything seemed brightly lit, which influenced the design. It was a contrast to then go to London where “everything felt sort of tall and narrow” with spaces more enclosed.

Cronkhite also enjoyed working the characters into the landscapes. She loved the scenes with King Julien, the lemur, who falls for a circus bear, Sonya. The couple tour the streets of Rome, stopping at the Vatican, the Spanish Steps, and Trevi Fountain. “To travel to those places and to be able to try to represent them in the film,” she says, “was so, so fun.”

TRAVEL TIP

After two years of shutdowns, European cities are beckoning travelers with history, culture, and cuisine. Pick London, Rome, Monte Carlo—or all three. A whirlwind tour of Europe might be just what the doctor ordered to heal the pandemic blues.

BAYOU BLISS

The Princess and the Frog

Walt Disney Animation Studios

Production Designer: James A. Finch

Landscape: The Bayou

Set in Jazz Age New Orleans, The Princess and the Frog offers inventive twists on a classic fairytale. When Tiana, the titular princess, turns into a frog, she and her love interest find themselves navigating the wonders and hazards of the bayou in a quest to regain their human forms.

Working under the direction of Art Director Ian Gooding, the film’s Production Designer James A. Finch notes that he and his team used several locations: the Garden District, the French Quarter, and the bayou. “What was interesting,” he says, “was when we went to New Orleans, it was the year after Katrina, and a lot of the trees had been stripped of all their leaves.” Finch and Layout Supervisor Rasoul Azadani realized that none of the trees they saw on that trip really reflected the Deep South bayou. So they went to South Carolina where they found a river that had “very unique pockets of combinations of vegetation coming together, and we could see where this would be special and isolated from the rest of the world,” says Finch.

Finch grew up in Florida, so he was already familiar with the swampy landscape of the Everglades, which he cites as one of the reasons he was given the opportunity to work on some of the bayou designs. “It was fun to dive into that and explore,” he says. “[The bayou] is a special place. It has its own unique elements. It’s a harsh place to live in for any animal, but it also has its romantic flavors.” To achieve these variable qualities, his team brightened up the palette in the daytime “so it had a lot of airy quality to it … a lot of natural light quality [that] made it fun and inviting.” For nighttime and the movie’s heavier moments, “We were just drying out the color,” he says, to give the landscape a more monochromatic feel. He also notes the importance of small details, such as the poetic look of hanging moss versus the typical small leaves on the oak trees. “It’s fun to think about all those elements that make something romantic, versus eerie, versus mysterious,” he says.

“[The bayou] is a special place. It has its own unique elements. It’s a harsh place to live in for any animal, but it also has its romantic flavors.”—James A. Finch

In the bayou Finch was excited by the size of the cypresses, with branches so heavy they touched the river bed before growing back up and tangling in the “elbows” that are part of the root system. But when it came to dimensions like this, he notes the difficulties. “When you’re looking at the scale of the [small] animals compared to the trees, you’re really looking at [just a section] of the tree.” How do you incorporate these shots with the bigger perspective so viewers can fully appreciate the grandeur of the bayou setting? One example is the character of Ray, a tiny firefly with a big heart and an extended family that magically lights up the swamp. Tackling the challenge of making such a tiny creature visible in a massive setting, Ray was like “a pretty big lightbulb flying around,” Finch says.

He also explains that it was difficult because the environment is all water. Often the characters were traveling through the bayou on the back of Louis, the trumpet playing alligator, but at other times, they needed a sand embankment or something else solid to stand on. One such place belonged to a voodoo priestess, Mama Odie, deep in the bayou. She lives in a shrimping boat lodged in a majestic tree. Finch says there were a lot of ideas about her abode, to make her space fantastical and different, and more than just a little hut in the woods. They had many iterations and artists elaborating on an initial design, and it felt so charming that they didn’t want to move away from it.

Mama Odie’s home also showcased something unique about the New Orleans area: the shrimping boats. This was just one way to satisfy Finch’s belief that in every film that looks at a specific culture, it’s necessary “to give accolades to particular aspects that are important to that world.”

TRAVEL TIP

The Princess and the Frog offers more than just inspiration for where to travel this summer. It also offers suggestions for what to do while there—eat! First up are gumbo or red beans with rice, followed by a plate of Tiana’s Famous Beignets.