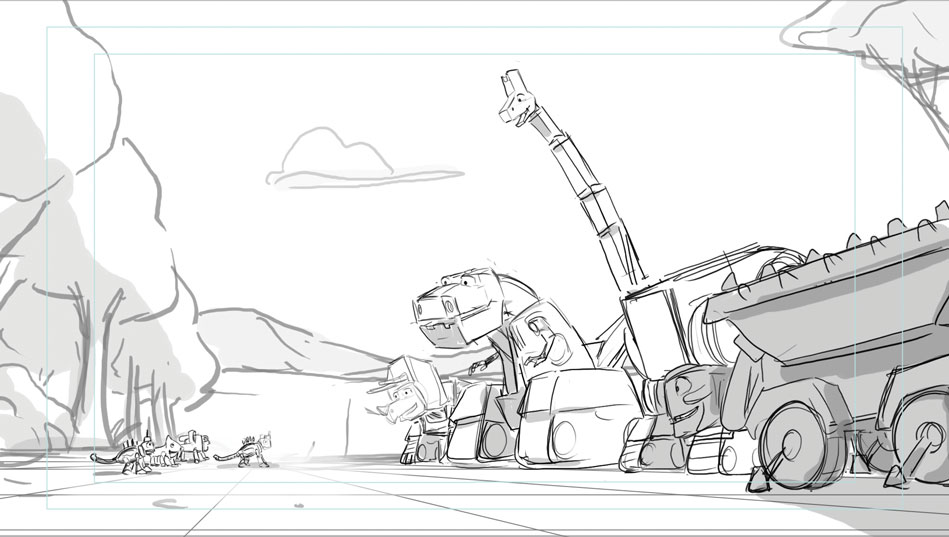

While working on the DreamWorks animated kids show Dinotrux Supercharged, Fill Marc Sagadraca helped create adventures for robotic dinosaurs with names like Craneosauraus and Garbageadon. Several years later, while working on the decidedly non kid-friendly Paradise PD, Sagadraca found himself depicting a rather different primeval interaction.

“We had a giant dinosaur having sex with a car,” recalls Sagadraca. “And in the opening scene, a character’s date gets urinated on twice. It was like, ‘OK, I’ve never done anything like that before. Check that one off the bucket list.’”

The gap between a Dinotrux Supercharged and a Paradise PD is vast, and it’s one which many artists have sought out as they move through their careers. If you have grown up watching cartoons, inevitably you have transitioned from G-rated content followed by more mature fare and then possibly returning to a new generation of daytime content when you have children of your own. But as a professional you can’t “outgrow” shows; to do so would be cutting off opportunities for employment.

As they train and enter the field, budding artists often end up watching a large spectrum of content—children and adult programming—with a more narrative- and design-focused eye before deciding what genre they want to pursue. Teaching life lessons to the pre-school set? Tougher, racier content that would make Bubble Guppies blush? Both? Something in between?

“People have short memories in this business, if you work on something for awhile, even five years. People forget you could do the other thing.”—Carol Wyatt

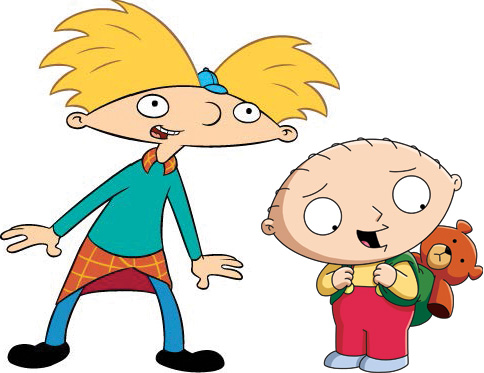

“We all got into it as kids, watching something we liked on Disney or the Tex Avery cartoons,” says Max Martinez, who worked on many of the Klasky Csupo shows like Rugrats and The Wild Thornberrys before moving over to Fox to storyboard on The Cleveland Show, American Dad! and Family Guy. “Not to be too cliché about it, but we all have that inner child that we fall back on that we use to go back and forth. I have a lot of friends in their 40s and 50s who have gone back to doing children’s cartoons, and they love it more than the adult genre.”

Veteran artists and writers who have worked extensively in both genres, say that they seek out their content of choice and that, in certain cases, the content finds then. Many contend that a strong visual storyteller should be able shuttle between adult and kids shows, provided she is able to adapt and—in some cases—to find a professional “in.”

That last part is important. As can be the case in any other genre of artistic creation, an animator can develop a reputation within the industry as primarily an adult content or child content specialist. It’s equally possible, after years in one medium, to get burnt out and look to switch gears.

“When I had been on children’s cartoons on Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network for awhile and I wanted to go onto a show at Fox. It was like I had to prove to them I was qualified to be on that show,” recalls Carol Wyatt, who has worked on such programs as Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends, The Cleveland Show and The Powerpuff Girls. “People have short memories in this business, if you work on something for awhile, even five years. People forget you could do the other thing.”

That adult animation often has a distinctly different look than children’s animation is by design but whatever the medium, a good story is a good story and has to hold an audience, say artists. The youngest TV viewer’s attention will not be held if the content isn’t engaging, and creating engaging content is a distinct talent.

“Adult animation calls for a rougher, relatively uglier, more gritty style,” says Ben Gruber, a writer and producer with credits in both genres as well as in non-animation. “Children’s animation, even if you’re telling a dark story, you need to make it look like a storybook, more aesthetically pleasing.”

Gruber acknowledges that within animated shows, the rules change from show to show, from network to network, and certainly from age range to age range. In adult shows, you can put your characters in jeopardy.

Stewie Griffin.

“For younger kids, a character can’t be in danger of falling in a hole,” Gruber gives an example. “In adult animation, you can have them fall in a hole and eat their own leg and people will think it’s hilarious.”

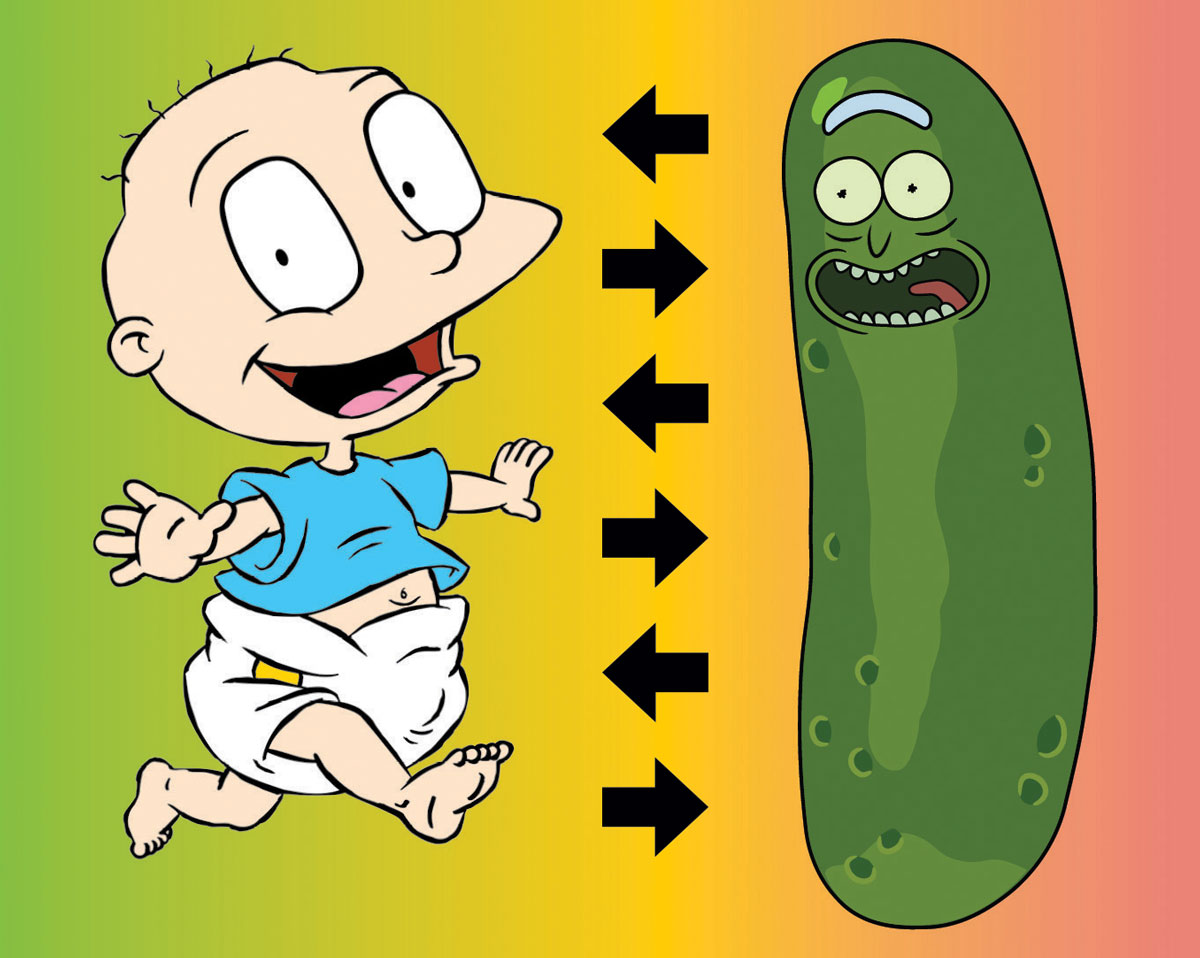

When she submits a portfolio, Wyatt says she is conscious of the work she is trying to get. It’s largely a common sense procedure. “I have a lot of everything so I don’t get stuck with one style,” she says. “Back when I didn’t have so many credits, it made a difference. There is a difference between adult shows and children’s shows both in terms of style and content. So I’m not going to post some of my raunchy Rick and Morty scenes next to Hey Arnold. That would be weird.”

“Going from adult to kids is not too hard, but going back can be difficult,” agrees Gruber. “Technically I’m very experienced but if I want to go write for The Simpsons, they’re going to really want to give me the once-over, have me submit a bunch of scripts and makes sure they think I can do it.”

Spec scripts can take up to three weeks to write. Though this practice has become an industry standard the WGA West and TAG have advocated for members to curb free writing.

Now in its 30th season, the Matt Groening- created Simpsons has served as a launching pad for (and in some cases has provided years of steady employment) to dozens of artists who have gone on to work on diverse shows. The same is true for long-running Fox series like Family Guy and the Seth McFarlane stable of programs. While one of those shows might allow you to storyboard your first fight sequence or indulge in some serious raunch, successful prime time shows also come with structures that artists must learn and follow. If a show is script-driven, the writers are going to know exactly what they want and they’re not necessarily going to allow a lot of improvising or experimentation.

When he joined Disney’s Gravity Falls after six seasons on Fox’s American Dad!, John Aoshima noticed the difference between the two environments immediately. Among other things, the production and budget demands meant a different type of workload and Aoshima’s directing output tripled.

“Basically on a prime time show, we had eight directors, and when I went to Disney it was a two director rotation, and that was a big change for me,” says Aoshima who directed multiple episodes for both shows. “I think prime time has a larger team just because of the budget. Also, they’re constantly rewriting and trying to stay up with the times in order to accommodate the constant rewrite changes they need. Production has to be able to adapt to that.”

“For younger kids, a character can’t be in danger of falling in a hole. In adult animation, you can have them fall in a hole and eat their own leg and people will think it’s hilarious.”—Ben Gruber

Wyatt agrees, maintaining that the high scene counts, tight deadlines, and constant rewriting of prime time shows can pose challenges. She was interviewed as she was completing her last day as a color designer for the upcoming Disney Channel show Amphibia to return to Rick and Morty, a show she had worked on previously. Although she has shuttled between both genres, Wyatt says she chooses her projects less based on kids versus adults than on the creative opportunity.

“I like to work on really fun styles, and so if I know a really great artist is doing a new show, and he’s trying to develop it and make it into something different and fun, then I want to be on it,” she says. “Rick and Morty is one of my favorite shows to work on. When I read those storyboards, I’m laughing out loud. People and personalities are also important.”

Most of the artists interviewed for this story said that—content restrictions notwithstanding—daytime children’s programming is the arena in which an artist may more frequently get an opportunity to stretch his wings. With less of an emphasis on narrative or of landing a joke, an artist may get more of an opportunity to submit an idea or be creative. New opportunities, such as the chance to direct, can often come with working on new shows.

“I created a series for Amazon called Little Big Awesome,” says Gruber. “Because it was me running the whole thing, I got to scratch every single itch of silliness. Pushing love and friendship and positivity to an almost absurd level so it becomes dark, that’s been funny for me.”

Although they acknowledge cases where they or their peers have encountered roadblocks, artists insist that a good artist should be able to transition between different mediums without difficulty, particularly given the number of new content popping up everywhere. They also acknowledge that the competition is fierce. An artist won’t end up employed on the staff of The Simpsons or SpongeBob SquarePants just because she can draw.

Writers and artists alike will need samples, according to Gruber.

“Especially if you’re a children’s artist trying to move into adult content, ” says Gruber. “Some shows are more visual than others and you’re going to have to be able to show them that you can play with animation.”

According to Aoshima, it has become something of a standard procedure for producers to give auditioning artists storyboard tests to see whether they can handle the creative demands of the show they are trying to join. The Animation Guild has been working with a testing committee of members to promote fair practices.

Following a lengthy stint as a layout artist on The Simpsons and Futurama, Aoshima moved over to Avatar: The Last Airbender, only to have it brought to his attention that his Avatar drawings were drawn with the proportions of The Simpsons.

“I didn’t see that until my director pointed it out,” Aoshima says.

In animation, as in other segments of the entertainment industry, Sagadraca admires people who can be chameleons.

“When I look at some of my heroes, a lot of the people I admire are people who can do everything,” said Sagadraca. “Someone like Ang Lee can do a Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and then Life of Pi. Every success in movies he has had is different from the one he finished. Part of me wants to model my career after someone like that, and not just be typecast as one thing.