“It was the first time I realized that animation could be more than just funny. It could be sad. It could be epic; it could be scary and beautiful. I was hooked,” says Farrell, who would work on shows including BoJack Horseman, Final Space and Duncanville. “I went home and checked out pretty much everything the ‘anime’ shelf at Blockbuster had to offer, which wasn’t much.”

Farrell’s story is not unusual among artists who grew up on Looney Tunes and Disney and were told that those styles—and not anything from Japan—would be the roadmap to industry success. It wasn’t so long ago that a love of Japanese animation—more familiarly known as anime—was something you kept to yourself. Consequently, a generation of people have passed around VHS tapes, devoured manga and videogames all while hiding their interests for fear of being razzed or discouraged from embracing those techniques if they wanted a career.

No longer. Those devotees of ‘80s and ‘90s anime have grown up, entered the industry and become game-changers. Some of the stereotypes of anime persist, but where one person sees oceans of blood, sexualized pre-teens and cuddly flying creatures, another finds vivid imagery, nuanced characters and deep philosophical themes. Blockbuster may have gone the way of the dinosaurs, but thanks to the Internet and streaming services, the anime “shelf” is loaded. Anyone wanting to binge watch has enough of a supply to outlast even an industry-shuttering pandemic.

Many of the long-running shows that have crossed over are indeed binge-worthy, given their themes, characters and structuring. Even at 22 minutes, a favorite program may leave you hanging off the proverbial cliff, desperately awaiting the next installment, the next season, the next iteration. And, if there is any absolute certainty about the cave of wonders that is anime, it’s that there will always be something new, something fresh, something mind-blowing.

Lovers of anime say you can recognize the influence of the style in a Teen Titan, a Disney robot or a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle. For so many people who work in animation, the progression of anime from its perception as a hallmark of nerd culture to a next frontier is still a work in progress.

Anime for Everyone

But there is anime for every age, every genre, every sensibility—action, sports, drama, comedy, fantasy, science fiction, even cooking.

“There’s Minky Momo, a magical girl anime that was really influential to me as a child. I still watch it,” says Erica Jones, whose work includes Home: Adventure with Tip & Oh and Adventure Time. “With that one, you could tell that it was just animators having fun animating crazy scenes. And at the center of it, there’s this really cute girl and she can turn into anyone. She can be anyone.”

Lamar Abrams, a writer and storyboard artist who worked on Craig of the Creek and Steven Universe, remembers seeing Voltron as a 5-year-old and then later sampled shows like Speed Racer and Astro Boy. For an artist who considered himself not especially detail oriented, Abrams found the aesthetics of anime that called for a simpler facial structure in characters appealing.

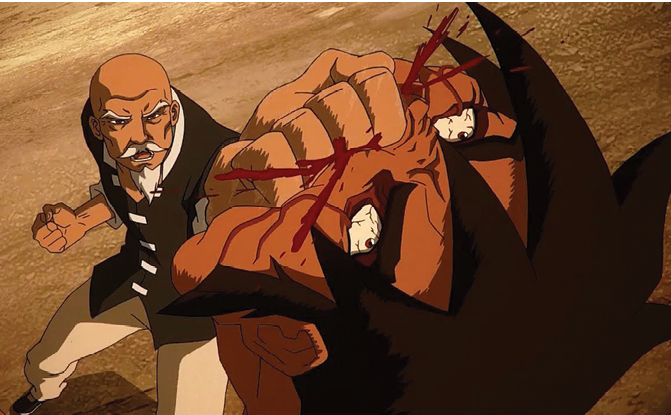

“[When Ninja Scroll was shown to me], my mind exploded. From the pure ‘what are you allowed to do with animation’ perspective, it’s like ‘Holy shit! You can make an old man fire bees out of his back, do kick-ass battles and have interesting adult themes.’”—Daniel Dominguez

“I found a lot of designs in Japanese animation to be very exciting,” says Abrams, who also created a comic based on the Dragon Quest video game. “They felt really fresh to me as an American who grew up on Bugs Bunny and other American cartoons in the ‘80s, like ThunderCats. When I was in school learning animation, they were pushing 3D because they said 2D was going the way of the dinosaur and we were not going to work on paper in the future anymore. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that can’t be because Japanese animation is so good,” he adds.

There will be detractors—sometimes even those teaching at art schools—who might dismiss popular TV anime as a stew of big-eyed characters, over-the-top emotions, an overindulgence of violence and hot young girls. But to those who have studied the art and artistry, the hallmark of anime is its ability to offer an infinite array of dramatic possibility.

“I wasn’t very into Disney. I was like, ‘Screw those cute lions,’” says Daniel Dominguez, a writer on SpongeBob SquarePants and the Powerhouse Studio-produced Seis Manos. “So when Ninja Scroll was shown to me, my mind exploded. From the pure ‘what are you allowed to do with animation’ perspective, it’s like ‘Holy shit! You can make an old man fire bees out of his back, do kick-ass battles and have interesting adult themes.’”

Visual tropes or a compliment?

Depending on who you ask, characterizing a show as being “anime-influenced” is either the highest of praise or an insult. Many assume you’re talking about the style’s visual tropes—the big eyes and hyper-violence—rather than the deeper themes or multi-layered characters. Tom Riffel, whose most recent work was as a retakes director on Paradise P.D., often finds himself feeling pessimistic about the very perception of something being labeled “anime-influenced.”

“So if someone says to me, ‘Oh, this is anime-influenced,’ the first thing I think of is, ‘Okay, you just want it to look like anime,’ going back to just the visual aspect of the show,” says Riffel. “I think that now that anime’s a little more popular and more mainstream, those kind of negative [characterizations] are going away a little bit because people are seeing more anime that doesn’t have that stuff.”

Another popular term within the industry is “anime-adjacent,” according to storyboard artist Alan Wan. Wan grew up in Hong Kong where he watched a lot of anime during the ‘80s and ‘90s. He singles out the series Fooly Cooly (FLCL) as a show that has particular resonance during his time on Teen Titans and also on the Disney co-production Super Robot Monkey Team Hyperforce Go!

“Back when I was working on Teen Titans, that was actually one of the rare times where we embraced anime a lot,” says Wan. “FLCL has everything. Initially, when you watch it, you watch it for the wacky, really crazy action scenes, but once you dive deeper into it, there’s a lot of excellent filmmaking that we don’t really do in the U.S.”

Bravery in Storytelling

Followers of anime say that drawing a distinction between Disney and the animation of Japan is reductive. Many American artists who have worked for Disney or DreamWorks say they have drawn inspiration from Japan. On the features side, 2008’s Wall-E, a film with environmental themes that has no dialog for much of its duration, is the kind of movie that could have come out of Japan. And although it was inspired by a Marvel comic, 2014’s Big Hero 6 is an homage to Asian culture with its relationship between a boy and his protective robot that is set in the hybridized city of San Fransokyo.

Miyazaki’s influence in U.S. animation is far-reaching. In creating the flying sequences for 2002’s Lilo & Stitch, Director Dean DeBlois recalls drawing on influences of films like My Neighbor Totoro and Porco Rosso. The influence continued several years later as DeBlois and co-director Chris Sanders considered a key element of Toothless, the hero at the heart of How to Train Your Dragon.

“When we were starting out, we realized that there had been several movies with a human and a dragon and how were we going to differentiate this from others?” says DeBlois. “It was specifically a very Miyazaki inspiration for me to suggest that maybe the dragon was in some way damaged and the boy would have to create this almost da Vinci-like contraption that would supplement and take the place of the missing tailfin. It just kind of had a visual appeal to me that also injected some wonder into it and some wish fulfillment.”

To DeBlois, the hallmark of anime is its bravery in an approach to storytelling that is not influenced by marketplace considerations.

“There’s no overthinking of who the audience is,” he says. “It’s just about what would be spectacular, what would be emotional and what would really be resonant. And I think that has defined the audience and the popularity of the anime genre, within animation as a medium. Just because it feels unrestricted in a medium that often is quite restricted, because of the budgets that are required in order to execute them and put them out into the marketplace.”

Beyond Limits

Having grown up in Japan, Rie Koga has worked in the animation industries in both countries. When she got satellite TV in 1999, she had access to Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon and shows like Dexter’s Laboratory and the Powerpuff Girls. As her interest in American animation developed, Koga noticed the stylized designs, quick cutting and constant dialog of those shows. “It was almost like I was watching stand-up comedy,” she says.

“There’s no overthinking of who the audience is… It’s just about what would be spectacular, what would be emotional and what would really be resonant.”—Dean DeBlois

“Japanese animation has a bigger story arc,” says Koga. “Sometimes the characters die, even in kids shows. I got so scared by kids shows in Japan, but it’s a very normal thing.”

After working on multiple action shows in Japan, Koga moved to the United States in 2011 partially with an eye toward seeing how the industry worked. She studied at the Concept Design Academy and was hired as a storyboard artist on the Nickelodeon reboot of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Voltron: Legendary Defender.

In looking around the industry, Koga has noticed more American animated shows taking on some of the characteristics of anime like continuing storylines and weightier themes. “An example of that would be Steven Universe,” she says. “Those designs look cartoony, but it has a big story arc from beginning to end and sometimes it has very heartbreaking moments.”

Ian Jones-Quartey, a writer who has worked on both the Steven Universe series and movie agrees citing 1970s-era anime like Future Boy Conan and Lupin the Third as part of the influence of the show created by Jones-Quartey’s wife, Rebecca Sugar.

“A lot of the visual style was based on classic video games from the 16-bit and 32-bit era,” he says. “A lot of the art directors of those games were probably inspired by animation, Japanese and not.”

On his show, O.K. K.O.! Let’s be Heroes, Jones-Quartey says that the creation of a department specifically to bring in animators to do difficult shots is inspired by the model for Japanese cartoons. “I see that trend becoming very normal on a lot of Western shows,” he adds. “I think there’s a lot to be inspired by.”

“Seeing other countries unafraid to explore the limits of what animation can do, and what kinds of stories it can tell, can absolutely inspire us to follow suit,” agrees Farrell. “It’s the core of being an artist to see something cool and think, ‘Wow! I want to make something like that!’ I hope we do.”