-

Bryan Turner -

AnChi Shen -

Jerry Gaylord -

Pamela Hoogeboom

Moved by the murder of George Floyd, police brutality, and other tragic events of 2020, animation executives Dawn Yamazi and Deb Stone began percolating the idea of a book that would lay bare the inequities they were witnessing and offer hope for positive change.

They formed a small advisory board to explore initial ideas. Two TAG members—Storyboard Artist Jerry Gaylord and Story Artist and Character Designer Bryan Turner—were among the first people involved in a brainstorming process that would evolve into Art of Change in Support of Black Lives, a coffee table book that tackles hard historical moments, imagines an inclusive future, and celebrates Black triumphs and joy—all with the goal of inspiring dialogue and action.

More artists joined the project, and over the course of many discussions, it was decided that Past, Present, and Future would provide the framework for art and stories. Each artist was given a mostly random selection of five words related to a given time period. Small groups were then created, and they met in Zoom meetings, researching and finding the stories they wanted to tell through individual works of art.

“Everyone was free to interpret [their theme] however they wanted to,” Gaylord says. “We didn’t want to control what people created.” At the same time, each breakout group had a guide to ensure sensitivity to the subject matter. This process required truthful discussions, and so before the book was even published, it was sparking the kinds of conversations Stone and Yamazi had hoped for.

Gaylord especially appreciated that “everyone’s experience with these issues and themes is different depending on who you are. We don’t experience it the same way, and we wanted to be able to have all of [these varied experiences] present and accounted for.”

More than 100 contributors to Art of Change included numerous TAG members. Story Artist AnChi Shen was born and raised mostly in Taiwan. “When everything happened in 2020, it was a huge shock because I don’t know the past of this land that well,” she says. While she was in her breakout group she was also in her first job out of university. As she looked around her workplace, “it was pretty obvious, the difference in diversity,” she says.

“Speaking to AnChi, maybe she hasn’t experienced the same things Jerry or I have,” says Turner, “but she can reflect and say, you know what, I’m at work and I’m noticing things. Maybe I can speak to that.”

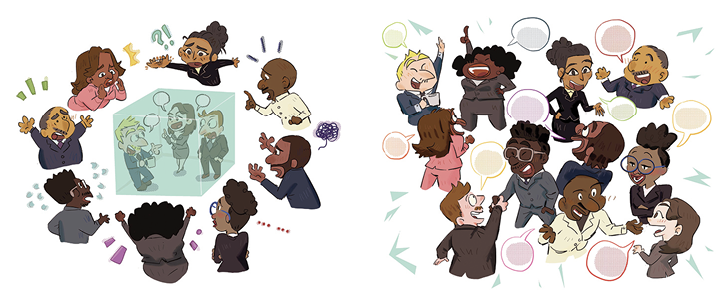

For her illustration, Shen came up with the idea of the proverbial glass ceiling as a glass box. Inside the box people are mostly white. Outside are people of color. But if you break the glass box, then everyone is in the same place and “everyone can feel empowered,” she says.

While Shen reflected on what she was witnessing, for Gaylord “it was really about processing what I was feeling at the moment,” he says. “For me it was all very personal.” While listening to public discourse, he kept hearing people say that the police aren’t bad, it’s just a bad apple here and there. “I don’t think those people remember what the actual saying is,” he says. “One bad apple spoils the bunch—not ignore the bad apple.” Gaylord chose to depict a Black boy horrified to discover that the apple he’s holding is rotten with monster police.

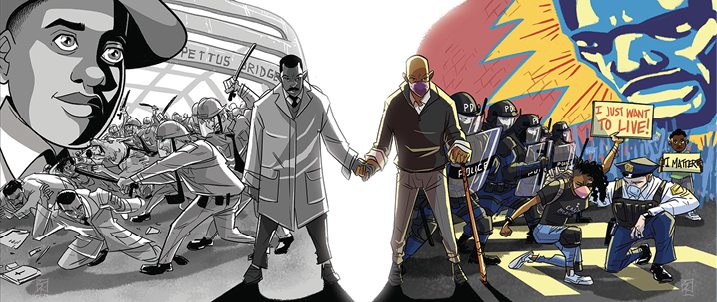

Turner took another path, interested in how differently people were reacting to what was happening in the country. “A lot of it was negative rather than focusing on what we can actually do to strive to make things better,” he says. His thoughts turned to Congressman John Lewis who experienced the struggle for voting and civil rights in the 1960s and the struggle against police brutality in the 2020s. “I can only imagine how he was feeling,” Turner says, “wanting to hold their hands and say, hey, listen, calm yourself young person, this is what we need to do in a civil, intelligent way so people can become educated.” The result is a portrayal of a young John Lewis holding hands with an old John Lewis, bridging the eras of Emmett Till and George Floyd.

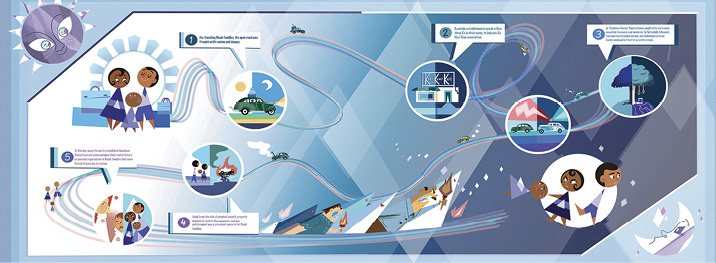

Each artist in the book has their own distinct style, but for Visual Development Artist Pamela Hoogeboom, a very specific style was essential to making a point. “I wanted to do something that on appearance seemed fun and friendly,” she says, “and when you get into the actual content you start to see the injustices, the horrors, the things that aren’t fitting into that Golden Book style from when you first looked at it.” She focused on Route 66 and the “sundown towns” where Black people were not allowed after sundown. “You’re drawn in by how colorful and cute and sweet this [seems to be], and as you go through it you get some pretty horrific facts. Hopefully that shocks you a bit,” she says.

A call to action, Art of Change creators and artists hope the book will inspire people to talk about race and inequity in America “rather than just banging heads,” says Turner. “It should be a natural discussion, [and] I think this book lends the opportunity for that.”

You can order a copy of Art of Change at www.OneWorldWe.com.

.png)