In epic stories, heroines never take a straight path from beginning to end. Raya and the Last Dragon is a classic example. Raya has a clear objective—find the world’s last dragon and save humanity from the evil Druun. She also has obstacles to overcome.

Because life has an uncanny way of imitating art, the production of Raya and the Last Dragon followed a parallel path. According to Director of Cinematography Lighting Adolph Lusinsky, there was a concrete goal from the start: “Latching the cinematography ideas, in particular with the lighting and camera, with the story arcs and the story thematics.”

Straightforward enough, except for this hurdle. What were those arcs and thematics? Originally, the theme circled around a broad concept. Head of Story Fawn Veerasunthorn says, “Over the course of the film, we were trying to find our statement about community. We tried different ways—is it about creating hope, inspiring others, working together?”

There were false starts and detours, but with the arrival of two new directors, Don Hall and Carlos López Estrada, and an additional screenwriter, Qui Nguyen, joining screenwriter Adele Lim, the theme began to gel. “We felt like this idea of trust would give us the specificity that the movie needed,” Hall said. “In a broken world, you can’t trust anybody, versus the world is broken because you don’t trust anybody.”

Once Lusinsky and the other departments had a theme they could reflect visually, they explored cinematography techniques to convey it. They created film LUTs inspired by the out-of-print Kodak 5289 film stock. “Trust had the most color and had less contrast,” he says, “[and] we had the grainiest, like 16mm grain, in the distrust. It’s much harder and more contrasty as well.”

“Over the course of the film, we were trying to find our statement about community. We tried different ways—is it about creating hope, inspiring others, working together?”—Fawn Veerasunthorn, Head of Story

“The strongest trust would [also] be the shallowest depth of field moments,” Lusinsky adds, with prominent bokeh shapes in the background. Lighting Supervisor Gregory Culp recalls how this works in a scene in which Raya is talking to her father, the one person in the world she trusts. “In order to portray that trust, we took the roof off of the kitchen, and one of the lighting artists, Steve Null, painted a dappled light setup that would hit very specific spots of the room.” Shiny objects were set dressed into the background—cans, pots, and pans with reflective qualities. This enabled the bokeh effect Lusinsky describes, giving the space warmth and keeping the focus on the intimacy between Raya and her father.

Just as trust was tested in the movie’s story, it was also put to the test on the production side. “We had planned on having a very heavy process of delegation,” says VFX Supervisor Kyle Odermatt. “That was a direction we talked about long before 2020. But when it came time to work from home, we actually doubled down. We got initial direction from the directors and then let the supervisors and artists really run with [it].”

Deliberate and Meaningful

Early on, Lusinsky says, he, Director of Cinematography Layout Rob Dressel, and Production Designer Paul Felix visited various departments and shared the cinematic vision for the movie, “so everybody on the show was really aware of what we were trying to do. Particularly with camera and lighting.” They discussed the intent behind the color scripts and the camera effects they intended to use.

Veerasunthorn says this kind of initial collaboration was new to her. “In other productions I worked on, I feel like we were just drawing. … Even though my department is happening so early on, and lighting is almost the last thing that happens, for us to be able to communicate back and forth, that helps.” Although her artists weren’t drawing details, she felt it was important to be conscious of the choices that were going to be made, and even the type of lenses that would be used.

Veerasunthorn recalls how learning about bokeh effects influenced her work on a scene showcasing the relationship between Raya and her father. “I was trying to be conscious about, I’m going to put the window behind him so they can put all the sparkle of lights. And I was drawing some props [that can] reflect light. Layout can do whatever they want with it, but at least in my end I’m going to be keeping in mind what the lighting and cinematography team is trying to do.”

As a result of this inclusive approach, after the pandemic hit and everyone started working from home, the production became “this exercise in trying to see how every shot could be deliberate and meaningful, and every creative choice we were making was really pushing on those ideas,” says López Estrada.

Many of those ideas were shaped in part by a wide range of live action movies. It became a house joke that a meeting with Hall would inevitably include a Spielbergian reference. And a heavy influence on Lusinsky was Babel, with its different storylines shot in different settings with different film stocks. “For example, in Tokyo it was a much finer grain film stock. And when you were in the Middle East it was a very, very grainy film stock.”

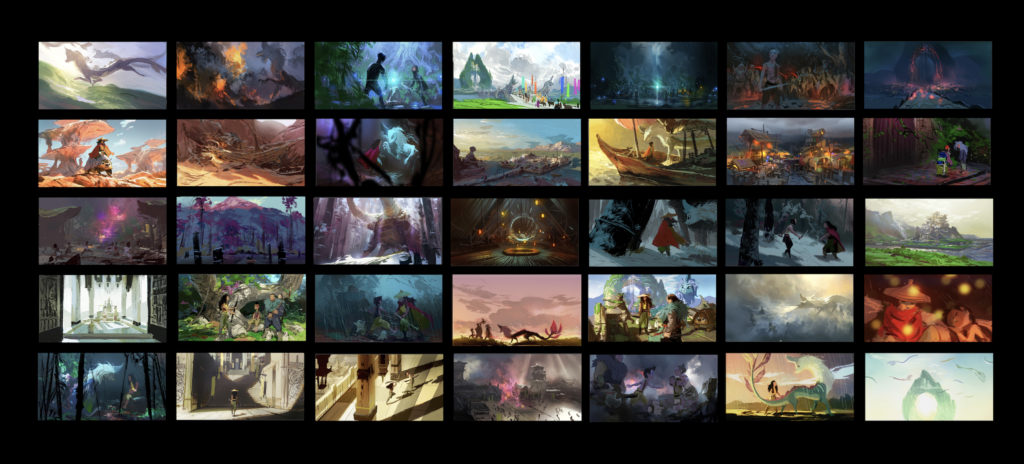

This was particularly applicable to the five lands in which Raya takes place: Tail, Talon, Spine, Heart and Fang, together comprising the dragon-shaped fantasy world of Kumandra. As Raya undertakes her epic journey, traversing the lands, each gets its own different application of film stock and film grain to reflect its place in the overall theme of trust and distrust. Culp says this is where a lot of work was done early on, and where the color script played an important role to figure out how all the colors in all the worlds could be distinct but still hold together.

Felix was responsible for laying this groundwork with a time of day color script. “[This] was the first visualization of how everything sort of meshed together,” he says. “Then we got a lot more specific when each sequence went into production. I would prepare some color keys to give everyone an idea of where we were heading, trying to create … a design language [for each land] and what their predominant color palettes would be just to keep them apart visually. … But what ties [them] together is the way we organized the color and the lighting cinematically. Because everything is subordinate to the tonal design.”

Library of Light

Kumandra is inspired by the countries of Southeast Asia. Along with a mission to portray the region’s traditions, cultures, art, and architecture as accurately as possible, the team also aimed to authentically create the “feel” of the region. Early research trips were taken, sparking discussions about humidity, the thickness of the air, and the way elements such as mist over water diffused light so close to the equator. They wanted to include all of these details in the movie, and to address this challenge, effects created an atmospherics library in pre-production.

Culp says research about the different kind of volumes needed in the film led to Lighting Supervisor Ryan DeYoung putting together “panels and images that would describe kinds of volumes … volume that sits over the top of water, for example. And … mist, like outside, on a rainy day, on a dry day. What it would look like for dust, coming from sand, kickups of sand? Then we talked to FX about getting some of those put into elements that we could bring from a stockroom for placing into our shots based on the different worlds.”

The result, Odermatt says: “Lighting had free reign to apply all of the atmospherics library to be able to do what they needed to do compositionally.”

“As we went into our initial sequence lighting, we’d grab those atmospherics and start dressing them into the set,” Lusinsky adds. “It’s cool because atmospherics help simplify the image, and really help you focus where you want.”

One example is a scene in an open-air market with lots of food stalls. Odermatt says the lighting team was able to add elements from the atmospherics library “to make it feel like there’s billowing steam from cooking pots that may or may not be seen. It has that sort of layered feeling if you’re walking down the food aisle in any kind of busy night market situation.”

“You’re supposed to have your critical eye super sharp, but that was the hardest part to me. [Raya] looks like nothing else we’ve seen, and we’re just so proud… It’s definitely the best-looking film we’ve ever done.”—Don Hall, Director

“To actually have lighters who can use those tools like a cinematographer to create soft shadows, silhouettes, block out part of the image with a library of effects, it was astounding,” says Felix.

In addition, Odermatt says that without these pre-made elements for lighting to use, scenes would have had to go without because the effects department was too busy working on other challenges.

Another area the atmospherics library came into play was with Felix’s color scripts. Culp says, “He would give us visions, through his paintings as color scripts, of what he would expect from light dispersion and what color would do in an area at what time of day.” Using Felix’s art color cues and direction, the lighting artists would start experimenting, taking volumes from the library to see what could be achieved.

Along with the library, effects and lighting also overlapped significantly on the Druun. Like a plague or a virus, these intangible spirit beings take life from people and turn them into stone. Lusinsky says, “What’s cool about the Druun is, overall, they are these dark kind of organic things with this hot core inside of them. That tied in to the thematic really well, because it created a lot of contrast in dark and light areas.”

Effects provided locators and lights inside the effects-driven Druun, which the lighting artists would use to illuminate scenes. Because the Druun had this internal lighting component, Odermatt says, “All the collaboration between lighting and effects had to be very, very tight … If you’re doing a dust cloud in the background, compositionally it’s important, but it’s not going to contribute to the lighting setup in a significant way. But when you’re going to put a big Druun compositional element that has a strong lighting component to it, that is critical to the outcome of the scene when it comes to the overall lighting scheme.”

“If we hadn’t had that atmospherics library, it would have been really challenging to get the Druun characters to read,” Lusinsky adds. “We developed these different atmospherics, and you can just imagine a little menu that says rolling mist, and you choose it and the atmosphere would show up in your shot and you could move it, place it wherever you need it.”

This was important, Culp says, because you can easily get distracted by the Druun when your gaze should be on action that is going on elsewhere. “So it’s all about looking at the image and trying to organize it in a way that’s perceivable to the audience member so you’re not distracted by five, ten Druun, when you’re supposed to be noticing the character in the far foreground atmospheric.”

With each obstacle tackled and overcome, the production’s epic journey neared its end, and the trust that had been tested from the top down paid off. When Hall and López Estrada finally saw the finished product, Hall says, “You’re supposed to have your critical eye super sharp, but that was the hardest part to me. [Raya] looks like nothing else we’ve seen, and we’re just so proud. … It’s definitely the best-looking film we’ve ever done.”