In January of 2018, Melissa Cobb, Vice President at Netflix, told Jorge R. Gutiérrez to pitch something he didn’t think he could get made anywhere else. He offered a sprawling idea about a Mesoamerican warrior princess, and to his surprise Cobb said go for it.

“I remember driving home that night and telling [my wife] Sandra,” says Gutiérrez, whose past projects include El Tigre and The Book of Life. “She was like, are you sure that’s what she said? I’m like, yeah, pretty sure. I’ve worked in Hollywood a long time. I’ve never had my dreams come true just like that.”

It also helped that the time was right. “I’m 46 now,” he says. “Earlier in my career, I did not feel worthy.” He wasn’t ready to take on the issues that his dream project, Maya and the Three, explores. Patriarchy in Latin America. Parents making mistakes so it’s up to the next generation to fix things. The misinterpretation of certain teachings over time. Sacrifice as the most noble thing a person can do for something greater than themselves.

Brimming with deep themes, this tale of Maya’s quest to recruit three legendary fighters, challenge an ancient prophecy, and save humanity from vengeful underworld gods is also awash in eclectic influences—Incan architecture, spaghetti westerns, hip-hop, Aztec floating gardens, telenovelas, heavy metal, Chibi anime, Bollywood, cholas, Hong Kong flicks, low riders. The list goes on.

But if you ask Gutiérrez, who is also the director and executive producer, if there’s ever such a thing as too much, he’ll reply: “Everybody who keeps saying less is more—I say, no! More is more!”

This is why an epic, nine-chapter, four-and-a-half hour, animated fantasy “event” perfectly suits the idea that had been swirling around in his brain for years.

Back when he was a kid, Gutiérrez asked his father: Why are we both named Jorge? “My dad is quite the character,” he says. “He took me and showed me an art book with a painting, St. George Kills the Dragon. And he goes, George is Jorge, and Jorges kill dragons. You are going to kill dragons. I was like, what?!”

As Gutiérrez grew up, he fell in love with The Lord of the Rings, ancient mythology, and fantasies about witches and warriors fighting dragons. “I would read those books and watch those cartoons and see those movies,” he says, “and I kept thinking, man, if that camera would just go south, I bet there’d be people like us.”

He was right, and as he learned more about the mythologies of Mexico, Latin America, and South America, he was fascinated to realize that a god that had one name under the Mayans might be the same god, but with a different name, under the Aztecs. “Just like Roman and Greek mythology. You start seeing overlaps. You start going, oh, this is like greatest hits.”

His love for a mixed-tape version of storytelling also comes from going to school in the U.S. when he was young. Every weekday he would walk back and forth across the border from his home in Tijuana, passing vendors whose stalls were filled with a mélange of wares. “Aztec sculptures next to Darth Vader,” he says. “Then Marilyn Monroe sitting with Pancho Villa. So seeing all of those things together, that was a huge influence on me. It made having Mickey Mouse next to a Mayan god be normal. We were used to seeing [that]. It was our culture. The mix of cultures.”

As the idea for Maya and the Three grew, Gutiérrez’s obsessions with pop culture and mythology united with his passion for the Mayans, Incans, and Aztecs, as well as modern-day Caribbean culture. But as intrigued as he was by all of this, he didn’t want to do a straight history.

“Fantasy is definitely the foundation,” says Production Designer Paul Sullivan. “The history was for the sake of being informed. You’ve gotta know the rules before you break the rules kind of idea. From my perspective … I wanted to make sure I knew a lot about each of these cultures so the decisions we were making in design were intentional departures that would be based on the story.”

He also describes his deep dive into historical research as a North Star that helped him use history when it did serve the story. One such example was learning that “the Mayans are credited by some scholars with the discovery the Golden Ratio for proportions. They were mathematicians, they were very intelligent, so we used that idea of shape proportion balance. We put it in the doorways. We put it in the tree combinations. We put it in the bricks and some of the design elements. [It’s] an artistic principle that a lot of people follow.”

Building Character

Maya hails from the Kingdom of Teca, where her father and mother serve as king and queen. Her mother was once a famed Eagle Warrior, and Maya doesn’t understand why they don’t want her to be one, too. She is a rebellious teenage princess who was born from the contradictions Gutiérrez found between his lived experience and the lack of female heroes in Mexican folk tales. He calls his wife, mother, and sister “real warriors.” Because of this, he says, “I wanted to hack the popular culture and create this myth about Maya.” He explains he chose the name because it exists around the world, from Africa and Asia to Europe and Latin America. “She was to be every woman.”

Maya is strongly based on Sandra Equihua, Gutiérrez’s wife, who served as Creative Consultant as well as Lead Character Designer along with Gutiérrez. Also hailing from Tijuana, Equihua met Gutierrez when he was 18 and she was 17—at her most rebellious stage. “I think he really liked that,” she says. “I had to go against [my parents] rules in order to live. So he decided to take that part [of me] and inject it into Maya.”

Like Equihua’s parents, Maya’s shelter her. But Maya, Equihua says, “thinks adventure is life. And vice versa, life is an adventure. You gotta go out there, and you gotta go find yourself. In order for you to live and for you to learn you gotta make mistakes. And she does make a lot of mistakes. She’s not the perfect princess. She stumbles a lot.”

Maya is a conflicted character, and this is deliberately reflected in her design, beginning with her partial buzz cut and lopsided half-bob, showing that she is torn between being a princess and being a warrior. It’s also represented in the Eagle Claw club passed down from her father, a weapon that weighs a little too much for her, just like her responsibility to become a queen.

These are the kind of thoughtful details that help capture each character’s story, and as with everything in Maya, the choices are deliberate. For the creation of Maya’s mother, the Queen of Teca, “we wanted to make [her hairdo] look regal,’ Equihua says, “and I always thought that antlers look like crowns. I thought, wouldn’t it be beautiful if she was wearing a crown of her own hair that almost resembled antlers, tied up with different colored ribbons?”

The ribbons were inspired by Equihua’s family heritage in the Mexican state of Michoacán where the indigenous women perform a dance wearing long braids intertwined with brightly colored ribbons. This, combined with the antlers, is an example of Equihua leaning into the story’s magic, which meant, as far as she was concerned, “the sky’s the limit.”

Breaking Barriers

One of the biggest challenges was uniting the intricately detailed characters with the epic-scale backgrounds. “We wanted the environments to feel rich and supportive of the characters, but not compete with [them],” says Sullivan. The production team sought ways to balance cultural inspirations with character designs so that “each of [Maya’s five lands] is really representative of a particular character or a particular group of characters and a particular culture.”

“We wanted the environments to feel rich and supportive of the characters, but not compete with [them]” —Paul Sullivan

To make these differentiations, the representation of different color palettes was considered early in the process, after assigning color to each character and world. Sullivan explains that the symbolism of the assigned color would influence when a character was more represented in a scene by that character’s color palette becoming stronger.

For example, when Maya came into contact with an antagonist, color proportions were used to reflect the dynamics of the relationships and which character was dominant. And in the Kingdom of Teca, where there is a large volcano behind the city—whenever the antagonist came into that world, the volcano changed the color of the sky.

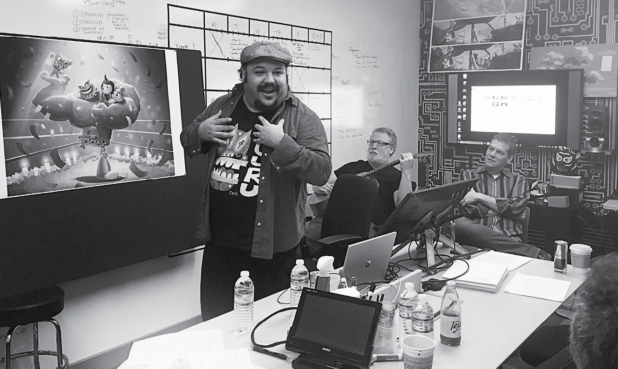

To help the artists understand this storytelling better, Head of Story and Co-Executive Producer Jeff Ranjo explains that there were table reads to give them “a sense of how [scenes] should be played.” Then the artists could ask questions or toss out ideas.

The opportunity to take part in the creative process impressed Sequence Director and Story Artist Rie Koga, who bonded with Gutiérrez over their shared love of vintage anime. “Jorge gave us enough information of what he wanted to see, but after … he gave us lots of freedom. This [was my] first opportunity to work on stories and character development.”

Working this way—unfettered within a framework—resulted in lots of fun results, from a scene done in cutesy Chibi anime depicting Maya’s naivete to split-screen fight scenes to emphasize two characters’ reactions at the same time. In one case, Gutiérrez wanted to experiment with aspect ratios to simulate a wide screen. He created fake black bars on the top and bottom of the screen, and when the action happens, Ranjo explains, it will break past the bars. “When there’s a hit, Maya’s Eagle Claw will [seem to] break the screen and go past it. [It gives an] illusion of 3D. To give it more of a visual explosion. Whoa, it’s jumping off the screen.”

Encouraging his team to push the limits of how to present emotional beats in animation helped Gutiérrez underscore the philosophy that serves as Maya’s through-line—If it is to be, it is up to me.

“It’s an ancient saying,” he explains, “and it translated very well in Spanish, it translated very well in English, so immediately I’m assuming it’s going to translate very well all over the world. I love this idea that there’s a million things, but it’s up to me to make a difference. I love that idea in the story where, yes there’s gods, and there’s armies, and there’s kingdoms, but it comes down to one person.” Whatever needs to be done—whether it’s saving humanity from underworld gods or reshaping mythology with the use of history, hip-hop, and heavy metal—“You have to do it yourself. [Then] when multiple people understand that, and they make a difference, they make a difference together.”