Strange World: Capturing Motion

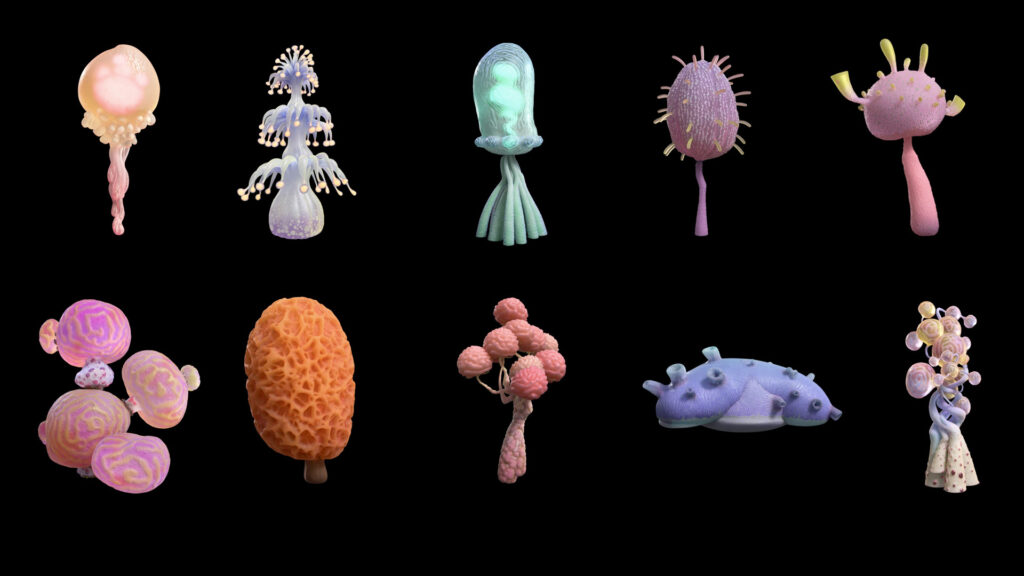

In the strange world of Strange World, millions of moving creatures and plants required filmmakers to come up with innovative techniques.

At heart, the movie Strange World is an adventure story with roots in classics like King Kong and Journey to the Center of the Earth. In the land of Avalonia, a farmer named Searcher Clade discovers pando, a plant that Director Don Hall describes as a “farm-to-table power source.” The cultivation of pando takes Avalonia from a kind of horse-and-buggy existence into the modern age.

But when the president of Avalonia informs Searcher that pando is no longer producing power, they set off to discover its source. Their journey takes them to the “strange world” of the movie’s title, a bizarre place that presented numerous challenges for both characters and creators.

Strike a Pose

When it comes to the movie’s characters, the Art Director Characters Jin Kim says, “I wanted them to look like my neighbors, my family. Like real people.”

Kim notes that Hall is a big fan of classic French comic book artists like Didier Conrad, and this influence can be seen in unconventional choices like the oval faces and bulbous noses of the Clade clan, from Searcher’s 16-year-old son Ethan, who is torn between farming and a life of adventure, to Searcher’s father, Jaeger, an explorer who disappeared on an expedition long ago. Kim also borrowed from early Hayao Miyazaki films in designing the costumes, which are “ambiguous in their time period,” he says, making viewers wonder if they are in the future or the past.

The purpose of Kim’s off-the-beaten-path details was to craft a more exaggerated look than is usually found in Disney’s contemporary, naturalistic-looking films. “Without those character designs being stylized, I don’t know that we could have sold the stylization we were going for,” says Amy Smeed, who served with Justin Sklar as Heads of Animation.

“[We were] trying to reconceive all the little in-house rules that we have about how we animate,” Sklar says. To get the look they wanted, they examined old-school Disney films, studying how to draw 2D design poses from every angle.

“We’re stepping through every frame and seeing, okay, here’s a key pose and here’s a key pose, and how are they getting from one pose to the next?” says Smeed. “What is the spacing? What is the timing? We were really dissecting and figuring out some fun ways that we could push on stylization for this show.”

Sklar says that the poses are much broader and describes lines that are long, simple, and flowing, with an emphasis on making “really beautiful transitions. The choices are surprising and unexpected, because they are often less concerned with reproducing reality and more concerned with big bold shapes.”

Smeed and Sklar also knew that if they pushed broad, comical movements, they had to do it in a way “where you weren’t going to laugh it off when danger showed up,” says Sklar. “If a character feels like you can drop an anvil on them and they’re gonna just get back up [and] be fine,” it’s difficult to convince an audience that they’re in peril.

The goal was to make interesting choices but ensure that the stakes felt real. “We were always looking for what was at the heart of these characters, so that even while we were stylizing, there was still that truth,” says Smeed.

Crowd Control

It’s not unusual for an animated feature to have large crowds in the backgrounds of scenes, but the ones in Strange World were unique. According to Crowds Supervisor Yasser Hamed, approximately 90 percent of the crowds in this film are creatures, from flying organisms shaped like red water drops to flying dinosaur-type beings. “That included the most diverse and largest scale of crowds we’ve ever done at Disney Animation,” he says.

Hamed estimates that roughly one in four shots has creatures in them—and in total, the movie uses approximately 56 million creatures. A notable example are the flying creatures that look like red drops of water. “Tens of thousands of these creatures, tightly packed in formation, produce a walkable surface for our main characters to interact with,” says Hamed.

In order to achieve this, he explains, “we developed a toolset within our department that would automatically instance thousands of creatures along an art-directed path and compress them tightly by using some collision-avoidance algorithms. Each creature had to behave and act in a unique way to ensure it had its own identity while still behaving as part of this overall formation.”

Because it would be impossible to animate the huge number of creatures used in various scenes by hand, Hamed’s team worked closely with the animation department to build differing “swim” cycles. These cycles were then incorporated into a simulation that allowed an entire formation of creatures to behave like a fluid. “We programmed the solver to artificially switch each character from one cycle to the next, blending it seamlessly,” he says. “Some cycles had creatures moving faster than others, while some cycles were animated so that they could break away from the main formation of characters, do something unique, and then rejoin the formation all automatically as part of the simulation.”

Along with the challenge of having these creatures come together to give the illusion of a solid surface, “another added level of complexity was that the speeds of the formations defined the speed at which the main characters would traverse through the scene,” Hamed says. To sell the physicality of characters walking or running on a moving environment “we had to work closely with the layout department to get the timing of the creatures just right as it played a big part in the cinematography.”

Going Green

Compounding this, the creatures weren’t the only things moving. Countless plants moved too, beginning with pando, which grows pods that can be picked and used as a power source. “Whenever you see pando on the screen, there’s always a glow, there’s always a motion,” says Sean Jenkins, Head of Environments.

Plants played such a physically active role in the story that an entirely new role was created to deal with them: Animated Environments Supervisor. In the way that Hamed dealt with creatures, Ben Fiske was assigned to come up with new ways to deal with the plants.

Typically, the effects department might animate the same plant a hundred times for different shots, according to Fiske, but the scale of Strange World made that approach especially unwieldy. So, they did animation in the asset phase, rather than in the production of shots. “What this means,” says Fiske, “is that I worked with a crew of really talented plant animators from effects and from tech animation, and they provided me with cycles.”

Software developers and technical directors then used these cycles to create libraries that enabled “animation on the entire environment,” Fiske explains. “If you think about the modern CG pipeline, we would wait until almost the last step to have plants animating. Instead, now, the directors are able to see animated plants [moving] pretty much right out of layout.” With so many plants in motion throughout the story, this enabled the filmmakers to visualize early in the process how the characters would interact with the background, making the production more efficient.

Fiske says that when he finally had the opportunity to flip a switch and turn on the whole environment, though, the immediate response was, “This is too much!”

Sklar says it looked like a rave, and Smeed says it was “distracting from the characters, and you always want to be with the characters.”

That the environment could compete with the characters was something the filmmakers had discussed, and Fiske was prepared for it. The system provided different options: low, medium, and high for every one of the plants. With 600 to 700 shots of moving vegetation, each shot was tailored by an artist in final layout. “[They] could either offset the animation of the plant or turn down the plant’s motion,” he says.

This solution did more than just “take the weight off a lot of really talented artists,” says Fiske, so they didn’t have to animate the same plant over and over. It also provided a manageable method of trial and error to find the best ways to forefront character performance. The result is a movie that honors animation techniques of the past and evolves technology of the future to tell the story of a family trying to figure out how much of the past to preserve, what kind of future to embrace, and how to find harmony between the two.

Puss in Boots: A Modern Furry Tale

Along with the expected blend of comedy and adventure, Puss in Boots: The Last Wish offers a surprising degree of pathos.

An existential crisis. Musings on mortality. If this sounds like the makings of an indie art film, think again. Puss in Boots is back, and this time around he’s dealing with some serious emotional baggage.

In Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, the beloved feline is down to the last of his nine lives, and his notorious bravado has been declawed, so to speak. “We get to see a more vulnerable, authentic, and emotional side to a character that usually never lets his guard down. It’s a fun space that I wasn’t expecting the character to go into,” says Production Designer Nate Wragg. “It doesn’t feel like a sequel to just say, hey, let’s see Puss in Boots do some more stuff. [This movie] explores the character in a deeper way while still getting all the adventure and comedy in there, too.”

Inspired by traditional fairy tale illustrations, the filmmakers faced the challenge of “updating an iconic character’s look without losing the familiarity of that character,” says Wragg. Every detail had to be carefully managed. Take Puss’s fur, for example. “Instead of being fine-detailed fur that CG would develop without any tweaks, we have a painterly treatment on it,” says Ludovic Bouancheau, Head of Character Animation.

This sounds simple enough, but Bouancheau notes the vast difference in how a shaved cat looks versus how a cat with fur looks. “The modeling department delivers the model of the character ‘furless,’ and the surfacing department delivers the fur—length, groom, color, etc. Both combined should give us the final design,” he says.

His team was adapting that Puss design while “trying to find a new visual treatment for the fur—a treatment that would change the way the fur’s volume would look in the end—so we had to be conscious about both aspects,” he says. “The delicate part was to know how to change the skin—shaved cat—to affect the fur that is attached to it without losing the design now that we introduced a third variable through the way we rendered that fur. A lot of back and forth and teamwork had to happen to find the right balance.”

At the end of this process, hand-sketched lines were digitally added to enhance the look and the motion, “things like impacts or sword hits,” Bouancheau says. “They were painted by animation either on an animation movie or early lighting movie, then taken over by our 2D compositing department for the final compositing over the final image.”

Bouancheau explains that the addition of the hand-sketched lines first came up as part of the step animation process used in some of the scenes because those lines would help complete the style when a scene shifted into step animation, “but we ended up expanding the use of those lines to many more moments in the movie. [We] even added brushstrokes over motion blur to enhance the look of some quick frames.”

The Fast and the Furryous

Meanwhile, Heidi Jo Gilbert, Head of Story, had to find ways to convey Puss’s complex personal journey through storyboards. “We really wanted the audience to feel the stakes and the weight and the emotion that Puss was feeling.” In describing one scene, she says: “You want to draw him small so he feels small on the screen. There’s storytelling through the composition that makes the audience feel a certain way.”

Gilbert notes that each scene required its own unique solutions because so many different tones were covered throughout the movie. Those tones weren’t just driven by Puss and his moods. The Last Wish has a significant cast of side characters, all with their own story arcs. Kitty Softpaws returns in an amped-up role, and she has her own personal demons, beginning with trust issues when it comes to Puss. Then there’s the endearing Perrito, a scraggly mutt who is optimism incarnate. His dream is to be a therapy dog one day.

Along with these two sidekicks, the villains build on classic fairy tale characters. “But they’re definitely reinterpreted for Puss in Boots,” says Bouancheau. The Goldilocks and The Three Bears crime family are scene stealers with their Cockney accents and rough ways, and mob boss Big Jack Horner is a sociopathic baby man using his plum pie business as a cover for his illegal dealings. Most notable, though, is The Wolf. “[Because] Puss’s fear is the engine that drives the whole [story],” says Gilbert, the film needed a character as spine-chilling as The Wolf to drive that fear.

Puss is in pursuit of the magical Wishing Star so that he can wish for his lost lives back. The problem is, most everyone else wants that star too because they have their own wishes to make. This storyline, while entertaining, required a certain mindfulness according to Gilbert. “We have to make sure we focus on Puss and we’re telling his story and not getting sidetracked by all these other fun characters,” she says.

Pitch Purrfect

As much as the filmmakers wanted to play with a traditional fairy tale aesthetic, they didn’t want a movie that looked aged or vintage. “Our approach was, let’s elevate the design and the world into this more contemporary illustrated space,” says Wragg. “What’s great about this is, it’s given it a little bit more of an artistic sensibility and flair across the whole scope of the film.”

Wragg says that one of the methods for achieving a film that feels like a modern fairy tale “was developing our surfacing style in the computer digitally.” Using digital painting techniques and custom digital brushes, “we would generate the look and feel of materials like wood, metal, cloth … in place of using real photos or reference on our models. In the end, it helped us create a digital feeling of wood or metal, without it being an actual image of wood or metal.” This was spread across the whole production. They created an entirely new surfacing library for the film, which “paved the way for an artistically driven look to our characters and environments,” says Wragg.

In addition, tools were developed that allowed artists to put a textured edge on any object in a 3D space. “Using this tool, we can control the level of asymmetry and irregularity at the object’s edge, which gives it a painterly feel,” says Wragg. “Much like if you took a paintbrush and swiped it. It’s a tool we can control as a dial. If we want more of it, turn that dial up. If we want less of it, turn that dial down.”

Overall, the dial was turned up for the perimeter of the frames to create an impressionistic look, and it was turned down in the center around the characters to make it more believable as they touched and interacted with objects and one another. The result, says Gilbert, was “stunningly beautiful. Multiple times we would stop a frame, and everyone would think it’s a painting. But no, it’s a still from the movie.”

Of course, no matter how gorgeous the art is, animation is about motion, and this was given the same attention to detail as the movie’s style. For emotional scenes, spline animation was used. This is typical of CG style, with the computer helping to fill in all the frames between keyframes, creating the realistic, smooth flow of movement needed to keep the audience immersed in Puss’s moments of sadness and despair.

For the action and fight scenes, on the other hand, filmmakers looked to the hyper-realistic but, at the same time, larger-than-life spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone. Framing included the dramatic use of close-ups and wide shots, and this is where the use of step animation came in. Dropping frames or holding a single frame onscreen for a count of two frames gave these scenes “a kind of choppy feel, which is more true to hand-drawn animation,” Gilbert says. This, in turn, heightened the tension.

While step animation has been used in features before—Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse being the most notable example—Bouancheau points out that Puss and Boots: The Last Wish used it to very different effect. This was a big part of the creative challenge. Not only breathing fresh life into a legacy character, but also expanding on existing tools in new and innovative ways.

“It’s easy to go to what you’re comfortable with or what you know,” Wragg says. “We know how to make a movie like the previous Puss in Boots. But really turning the style on its head and pushing it in a whole other direction, it’s a little scary, but at the same time it’s also exciting and rewarding.”